Abstracts

Aby Warburg. Mnemosyne Bilderatlas – Colloquium

Matthias Bruhn | Thomas Hensel |

Philippe-Alain Michaud | Werner Rappl |

Joacim Sprung | Giovanna Targia |

Claudia WedepohlSystem and Systematics. The beginnings of Warburg’s atlas project. |

|

Matthias Bruhn: Patterns

Warburg’s project on the science of gestures and memorial culture, which from today’s perspective appears to break the mould of traditional art history, was actually fully in line with the artistic research of the time from his point of view, particularly in terms of style critique and the evolution of form. Even the involvement of psychological, anthropological and theological approaches, which were extended in the Mnemosyne Atlas by genealogical and cartographical methods of representation and thought, acquiesce in the picture. However, as the current exhibition successfully shows, after several decades, the issues and the construction of the atlas are still puzzling and experimental in places. A key to this could be to search through another theorem which significantly influenced aesthetics around 1900, and which Warburg was particularly preoccupied with during his final trip to Italy.

Thomas Hensel: “Laboratory” and “central apparatus” or how Warburg’s picture atlas came into being from an engineer’s workbench

More recent Warburg research has shown that it is plausible that Aby Warburg’s historiography was formed in conjunction with technical media. So the structure of Warburg’s “Thinking in Pictures” (“Denken in Bildern”) was modelled by means of, among other things, imaging and image transmission processes such as cinematography, and the materiality of these media extends deep into Warburg’s historiographical and epistemological designs. This presentation aims to shed some light onto the origins of Warburg’s main work, his picture atlas. Based on archive discoveries, there is a theory that Warburg’s MNEMOSYNE picture atlas is owed to a special desk which Warburg deemed to be exceptionally valuable from an epistemological point of view. This presentation aims to reconstruct this desk and its significance for Warburg.

Philippe-Alain Michaud: »Mnemosyne« ways to dynamise the image

In Mnemosyne, Warburg experimented ways to dynamise the images : using the technics of montage and projection and the metaphor of electricity to set them in motion, he conceived of the screens of his Atlas as a cinematographic machine without apparatus. There is a crucial point in the genesis of Mnemosyne which has been all too often underestimated : the journey Warburg made in 1895-1896 to the Hopi Indians in Arizona. Elaborating a sort of theoretical fiction, in the Indian rituals, he was attending the reappearance of the Florentine Renaissance. That’s one of the possible meanings of the Erlebnis (Survival), a key concept in Warburg’s theory : the representation is not conceived as a concept or a form of knowledge anymore, but as a spectacle, not as Vorstellung, but as Darstellung – a shift which has since been the object of a real repression on behalf of his followers, and which explains how Warburg studies have provoked a real turn in the history of art and remains so infuential in the field of the media studies.

Werner Rappl: Image interference. Warburg, the uneasy.

The grace of God is in the detail – or was it the devil? Warburg’s analyses of origin, filiation and corruption contrast the pictures’ ominous claims to power with weakening strategies. He unveils migration backgrounds, discovers invaders and tries out new positions.

Constellations, maps, bloodlines: snapshots in a constant flow of displacement without an origin. Migration necessitates crossing borders. Aby Warburg followed the traces of analogies and threads of development to many places, including the USA, Italy and the Orient, and even his historical investigations led to far-off times and cultures, across the borders of scholarly disciplines and beyond. For this, he not only made use of new methods, but also opened up new sources. Aby Warburg experienced the risks of crossing these borders first hand.

These were reflected in the numerous versions of the atlas project. The origin is just as much evidence of this as the reconstruction attempts after Warburg’s death, their characteristic distortions and appropriations are shown in selected examples.

Joacim Sprung: Frame magic: The use of visual displays at the Kulturwissenschaftlichen Bibliothek Warburg and its legacy?

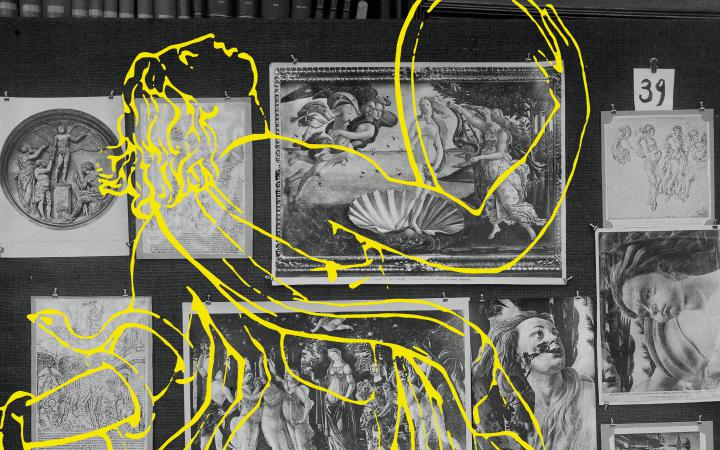

During 1913-1929 the German Art Historian Aby Warburg (1866-1929) and his associates at the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg (KBW) in Hamburg worked with a series of visual displays surveying the afterlife of Antiquity. Only photographs remain of their work with reproduced material pinned to hessian stretched wooden frames.

The frames did not only structure historical material for easier stylistic and typological comparison, but they also helped to create a visual proposal of a constructed historical space (Geschichtsraumconstruktion). At the same time, according to Warburg, the frames helped the motifs to become liberated (Luft für die Emancipation der Motive!) from history and the historical narratives. The frames and the visual displays where therefore almost seen as an Anschauungs-apparat or a magic frame that trapped and besieged the nomadic visual imagery that circulate between or in cultural systems.1 A device that could frame, reframe and ‘unframe’ the visual ideas and artefacts of the past, as well as being a window to future imagescapes and image-uses.

During the colloquim at ZKM in Karlsruhe I will discuss how the frames by Warburg/Saxl and others “Warburgians” (e.g. Kramrish, Clark, Quiviger etc.) where used as a visual framing device and how this image-use can find resonance in contemporary artistic practises, such as in the visual works by Elsebeth Jørgensen, Henrik Olesen and others.

Giovanna Targia: An “organically successful transformation of the heritage of antiquity”. Aby Warburg and Fritz Saxl against the nationalisation of Rembrandt’s art

When Aby Warburg gave his presentation on Italian antiquity during the period of Rembrandt on 29th May 1926, the images for which can be seen on panels 70-76 of the Mnemosyne picture atlas, modern perception of Rembrandt had reached a high point among both artists and in the research of art history. The discussion surrounding the particular features of Rembrandt’s art is part of a historical situation in which the definition of “national style” preoccupied a wider circle of people, and there was an increasing amount of ideologization of art-historical discourse.

Warburg’s interpretation benefitted from Fritz Saxl’s research, who had already dedicated his Viennese dissertation to the Dutch master. My presentation portrays a critical and comparative reading of texts by Warburg and Saxl to clarify what fascinated Warburg about Rembrandt. On this basis, key questions are formulated which were raised by the Rembrandt sequence in the picture atlas.

Claudia Wedepohl: System and systematics. The beginnings of Warburg’s atlas project.

Today, the Mnemosyne picture atlas is Warburg’s most famous work. Left unfinished in 1929 and – despite considerable efforts – never made fit for publication by his successors’ generation, no other work by Warburg has attracted so much attention. However, less well-known than the last remaining edition from October 1929, which consists of 63 panels, are the beginnings of the project which date back to 1905. In my presentation I would like to shed some light onto this period of time, namely Warburg’s documented attempts between 1905 and 1909 of systematically categorising the material collected in the Florentine Archives between 1897 and 1904. At the time, with these attempts (following different systems that had been developed in other disciplines), he already wanted to create a completely new alternative to the established history of art in terms of methodology.