2016-10-24

What Can Be Done with Images?

The renaissance of the picture historian, Aby Warburg

Walter Benjamin called him the “grand seigniorial scholar”: the interdisciplinary thinker and scientist Aby Warburg. Particularly in recent years, the focus has returned strongly to Warburg’s significance. His texts are being reread and interpreted.

The Hamburg-born art historian and cultural scientist, Aby Warburg, born in 1866, “a Jew by birth, a Hamburger at heart and a Florentine in spirit” (Warburg said of himself), provides information to this day on how we can read images. »Lieber Aby Warburg, was tun mit Bildern« (Dear Aby Warburg, What Can Be Done with Images?) was the name of the exhibition which could be seen at the Museum für Gegenwartskunst in Siegen from 2012 to 2013.

Warburg’s greatest scientific question was the influence of the ancient world on European culture. In Florence, he studied the art of the renaissance, the nymph portraits of Botticelli for example. In America, he studied the snake dance of the Pueblo Indians, where he found things in common, namely a “Denkraum der Besonnenheit” or a space for contemplation. However, he does not stop at what he sees in front of him. The folklore, art psychology, ethnology, anthropology – all these things move closely together in Warburg’s research.

»Mnemosyne Atlas«

We know the library – built up in Hamburg between 1925 and his death in 1929 and moved to London in 1933 – to be the lifework of Aby Warburg. In this library, Warburg compiled the »Mnemosyne Atlas«. In the entrance to the library, the Greek inscription »Mnemosyne« refers to the Goddess of Memory.

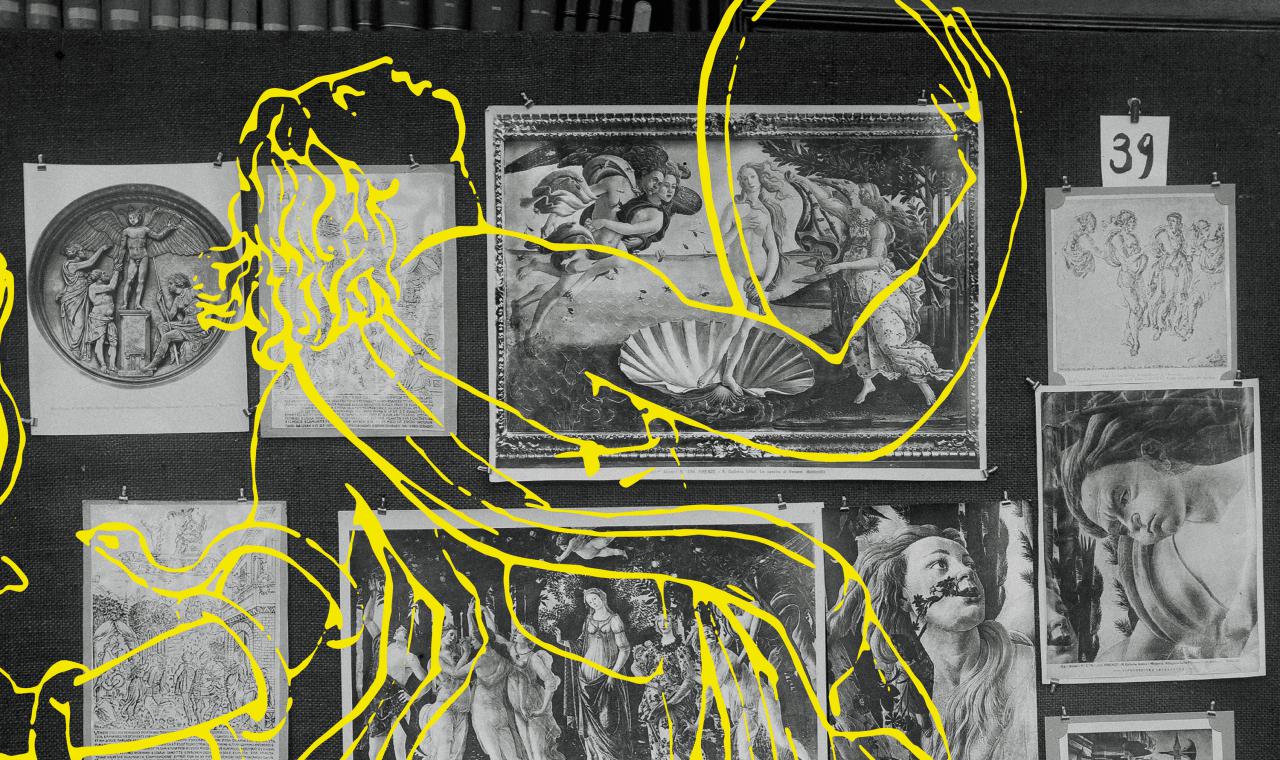

In this image atlas – a work in progress which was created over many years and constantly reconfigured – the thought processes of Warburg, his handling of images, becomes clearly illustrated. The 63-piece work – preserved today as photo documentation and as reconstruction – is a compilation of evocative images from art history and cultural history, which depicts a type of visual memory.

Only in recent years has this imposing, fragmentary compilation become the theme of various publications once more. For example, new books have dealt with Warburg’s medical history as a patient of the Bellevue Sanatorium in Kreuzlingen, where he was treated between 1919 and 1924 after a psychotic breakdown. A whole series of excellent Warburg books have been published, including a piece about the journey to Italy by Aby Warburg and his assistant Gertrud Bing. Even Warburg’s relationship with other thinkers, such as Ernst Cassirer and Albert Einstein has been the subject of new literature – or the role of Fritz Saxls, who was Aby Warburg’s librarian and later the director of the Warburg Institute in London.

“iconic turn”

After a number of years of relative silence – Ernst Gombrich’s great Warburg biography was published in 1979 – there has been a constant rediscovery of Warburg in the form of exhibitions, lectures and various publications over the last 20 years or so. This renaissance of Warburg and the Mnemosyne Atlas has been directly connected to the “iconic turn” since the 1990s – the recent orientation towards a science of images skilled in iconology, which brings together methods from very different disciplines.

Connected with the »iconic turn« term comes the concept of a power, significance and omnipresence of books and visual communication in the digital era that has grown immensely in recent years. Warburg’s interdisciplinary methods, which do not strictly separate the humanities and natural sciences, anticipate by decades the demand for a new, more versatile science of images, as is expressed repeatedly today.

Warburg is perceived today as the pioneer of the »iconic turn«, as the representative and founder of an iconological art appreciation. “In his name are linked hopes of making discoveries from impasses of specialist interests and intellectual modes,” wrote Roland Kany in the F.A.Z. back in 1999. “For Warburg, images are complex media of the memory,” continues the author – and emphasizes the volatile modernity of the art scholar, who recognized that culture is based on a capacity for remembering.

Not an art historian, but an “image historian”

Warburg noted in 1917 that he was not an art historian, but in fact an “image historian”, which sounds extraordinarily modern and attractive, even today. In times of ever growing digital image archives, Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas fascinates both cultural scientists and artists, such as the Hamburg-based “8. Salon” artist group, which has drawn closer to Warburg’s work in various ways.

Particularly significant – and current – is the fact that the ordering principle in Warburg’s image atlas is not based on visual similarities, but on “kinship” relationships, as Warburg called it. In his image atlas, we find figures of artwork, together with reproductions of stamps, promotional photographs, fashion photography – and even press photos.

A network of images, “search movements of a metaphysician, who strived to get to the very basis of all images,” as Wolfgang Ullrich writes in 2013 in »Die Zeit«, to conclude: “It is the essayistic, less the metaphysical, which makes Warburg attractive today”. “In an era,” continues Ullrich, “in which it has become usual in art to operate with the most diverse, often found materials, he supplies the paradigm for how images can be dealt with in vast numbers and extremely diverse styles and origins.”

And so Warburg’s image atlas could absolutely be received today as a piece of contemporary art: In its sketchiness, in the dispensation of wanting to present a finished whole, in the so differing provenance of the collected images. In recent years, a noticeable amount of photo art books have been published, which unify various images in a similar manner. However, Warburg had already found sources of this method of innovative combinatorics among his contemporaries. Above all was the Surrealist group which predestined the recombination and new combination of images into a preferred stylistic device.

About the Author

Marc Peschke lives in Wertheim at Main and Hamburg. He is an art historian, texter and fotography artist.

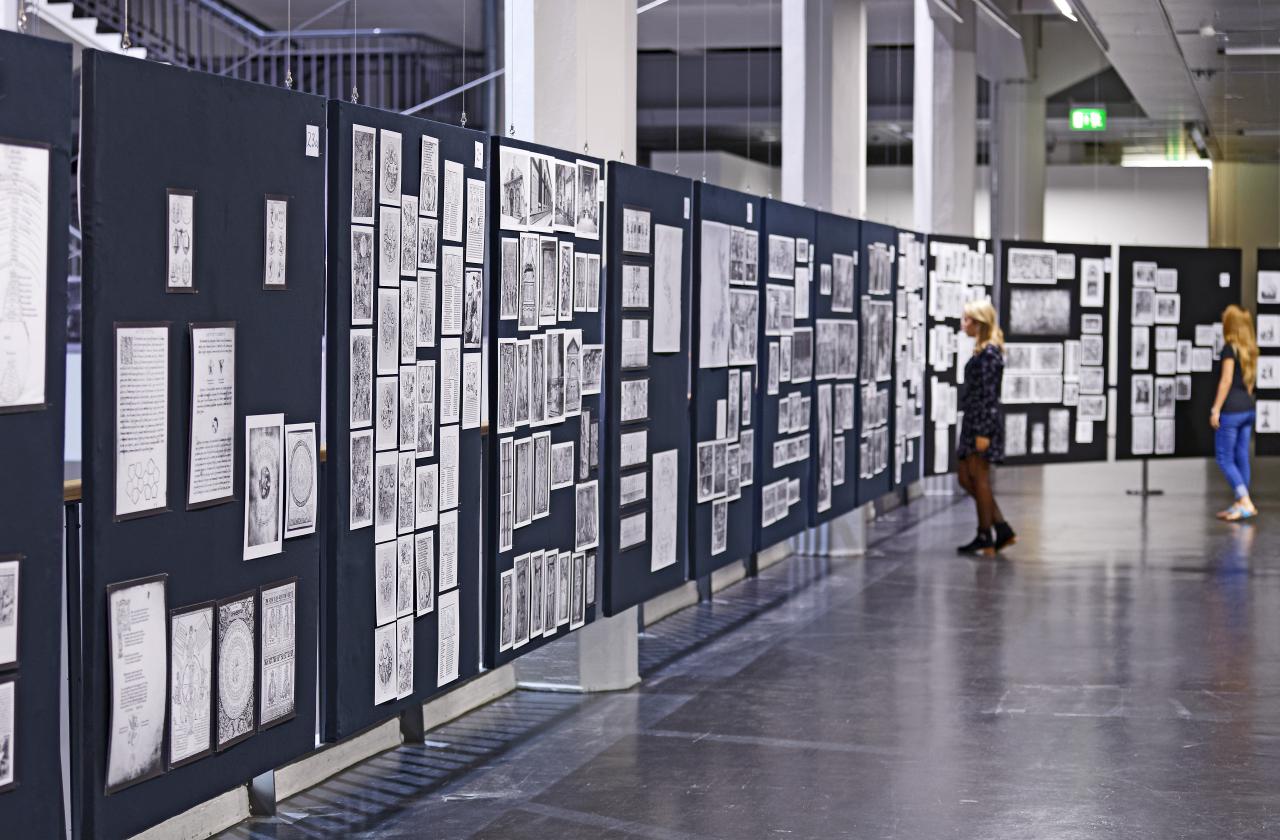

Aby Warburg. Mnemosyne Bilderatlas

Reconstruction – Commentary – Revision

01.09.2016 – 13.11.2016

ZKM_Atrium 1+2