From the munitions factory to a »culture factory«

Hallenbau A of the IWKA – Industriewerke Karlsruhe-Augsburg

In 1872, the Henri Ehrmann & Cie bullet casing factory in Karlsruhe is registered as a general partnership; the partners are Henri Ehrmann (businessman) and Leopold & Wilhelm Holtz (retired captain).

In 1878, a new owner takes over: Wilhelm Lorenz (engineer); the factory is renamed the Deutsche Metallpatronenfabrik Lorenz.

In 1883, the license is issued to manufacture live ammunition. W. Lorenz designs his own machinery to produce the shells. The Maschinenfabrik Lorenz Karlsruhe-Baden goes into mass production.

In 1889, the company is sold to Ludwig Loewe & Co and – together with the Pulverfabrik Rottweil-Hamburg and the Vereinigte Rheinisch-Westfälische Pulverfabriken – the Deutsche Metallpatronenfabrik corporation is created, which henceforth supplies the Prussian army with bullets.

In 1896, the company’s headquarters are relocated to Berlin and a branch office is set up in Karlsruhe. The company is renamed the Deutsche Waffen- und Munitionsfabrik (DWM).

Until 1914, acquisitions and takeovers mean the corporation develops into a company, which offers a virtually complete range in terms of »munitions«.

In 1914, the command for mobilization is issued by Kaiser Wilhelm II. The DWM, which has a supply contract with the German Reich in the case of war, begins operating at full speed ahead.

In 1914, architect Philipp Jakob Manz is issued with the commission to expand of the DWM factory in Karlsruhe. The initial plans are drawn up and the construction is declared a »matter of urgency«.

10 atriums are planned for Hallenbau A. Even though only 8 atriums with a water tower positioned pivotally are approved in December 1914, 10 atriums without a water tower are nevertheless built.

In 1878, a new owner takes over: Wilhelm Lorenz (engineer); the factory is renamed the Deutsche Metallpatronenfabrik Lorenz.

In 1883, the license is issued to manufacture live ammunition. W. Lorenz designs his own machinery to produce the shells. The Maschinenfabrik Lorenz Karlsruhe-Baden goes into mass production.

In 1889, the company is sold to Ludwig Loewe & Co and – together with the Pulverfabrik Rottweil-Hamburg and the Vereinigte Rheinisch-Westfälische Pulverfabriken – the Deutsche Metallpatronenfabrik corporation is created, which henceforth supplies the Prussian army with bullets.

In 1896, the company’s headquarters are relocated to Berlin and a branch office is set up in Karlsruhe. The company is renamed the Deutsche Waffen- und Munitionsfabrik (DWM).

Until 1914, acquisitions and takeovers mean the corporation develops into a company, which offers a virtually complete range in terms of »munitions«.

In 1914, the command for mobilization is issued by Kaiser Wilhelm II. The DWM, which has a supply contract with the German Reich in the case of war, begins operating at full speed ahead.

In 1914, architect Philipp Jakob Manz is issued with the commission to expand of the DWM factory in Karlsruhe. The initial plans are drawn up and the construction is declared a »matter of urgency«.

10 atriums are planned for Hallenbau A. Even though only 8 atriums with a water tower positioned pivotally are approved in December 1914, 10 atriums without a water tower are nevertheless built.

Form follows function

View into one of the empty atriums

© Municipal Archives Karlsruhe

The architectural concept of Hallenbau A and its implementation correspond to the principles of the progressive industrial architecture of that time. Based on a reinforced concrete skeleton, the Hallenbau has a floor area of 312 m x 56.4 m and is 25.8 m high, with a usable area on the ground floor of approx. 16,500 sq m.

The industrial building fulfils two basic functions: It acts as a functional building and production facility, which aims to effectively produce goods. It is also a chance for the factory owner to express himself.

To design the enormous dimensions, Manz, as the architect, gives the building a rhythmic configuration. Six avant-corps, each with a width of 12 m, are built at intervals along eight grid fields (each 48 m), into which the stairwells are relocated. The basic construction element of the building – the external pillars – are arranged rhythmically. The heights between the floors gradually taper towards the top. Daylight floods into the halls through the large windows.

The architectural design produces a double-comb floor plan, which provides major advantages for operations: in the long buildings that act as the backbone, the material, personnel and information flow is processed, while the material processing and machining is carried out in the transverse buildings.

The railway tracks for the works railway (in which you are now standing and which still trails through the entire building), makes it possible to deliver and transport heavy goods.

The building plans for the first construction stage (eight atriums) envisage 750 people per floor (500 of which are to be women). In this way, the workers access the building through decentralized entrances.

An enormous increase in production is reflected between 1914 and 1918 in a fast-growing number of employees: While there are 6,000 workers in 1915, this figure grows to 9,000 just one year after, with more women being employed than men.

Between 1915 and 1918, Manz builds a new factory building on a surface area of 62,000 sq m; the factory expansion involves a total of 8 new buildings.

The final acceptance of all the new buildings and the official start of operations doesn’t take place until 1918. This is too late for armament production. The reasons for the delay are the supply difficulties, in particular, and the lack of workers, as is usual in war times.

In 1922, the company is renamed Berlin-Karlsruher Industrie-Werke AG (BERKA) – to correspond nominally to the stipulations of the Treaty of Versailles.

In 1928, Günther Quandt takes over the company. In the foreword of the anniversary publication to celebrate 50 years of the corporation, he writes »In this way, however, it was possible to provide the Führer at the point of his seizure of power with a factory, in which the production of weapons could be immediately resumed on a large scale«.

In 1936, the Treaty of Versailles is openly breached: The company bears the name »Deutsche Waffen- und Munitionsfabrik AG« (DWM) once again.

Countless slave laborers have to work on producing munitions during the Third Reich in inhumane conditions.

In 1949, Harald Quandt takes over as head of the board following the Second World War. The company now bears the name »Industrie-Werke Karlsruhe AG« (IWK).

From 1970, the company is known as »Industrie-Werke Karlsruhe Augsburg AG« (IWKA). From the initials of the acquired company »Keller und Knappich Augsburg«, IWKA is later renamed KUKA (2007).

Due to the relocation of production to the outskirts of Karlsruhe, the premises become an industrial wasteland in the 1970s.

The industrial building fulfils two basic functions: It acts as a functional building and production facility, which aims to effectively produce goods. It is also a chance for the factory owner to express himself.

The ground plan is amazingly simple and unique in shape to date:

- Two long buildings, running parallel from north to south.

- Eleven crossovers, which connect the long buildings together and incorporate the atriums.

To design the enormous dimensions, Manz, as the architect, gives the building a rhythmic configuration. Six avant-corps, each with a width of 12 m, are built at intervals along eight grid fields (each 48 m), into which the stairwells are relocated. The basic construction element of the building – the external pillars – are arranged rhythmically. The heights between the floors gradually taper towards the top. Daylight floods into the halls through the large windows.

The architectural design produces a double-comb floor plan, which provides major advantages for operations: in the long buildings that act as the backbone, the material, personnel and information flow is processed, while the material processing and machining is carried out in the transverse buildings.

The railway tracks for the works railway (in which you are now standing and which still trails through the entire building), makes it possible to deliver and transport heavy goods.

The building plans for the first construction stage (eight atriums) envisage 750 people per floor (500 of which are to be women). In this way, the workers access the building through decentralized entrances.

An enormous increase in production is reflected between 1914 and 1918 in a fast-growing number of employees: While there are 6,000 workers in 1915, this figure grows to 9,000 just one year after, with more women being employed than men.

Between 1915 and 1918, Manz builds a new factory building on a surface area of 62,000 sq m; the factory expansion involves a total of 8 new buildings.

The final acceptance of all the new buildings and the official start of operations doesn’t take place until 1918. This is too late for armament production. The reasons for the delay are the supply difficulties, in particular, and the lack of workers, as is usual in war times.

In 1922, the company is renamed Berlin-Karlsruher Industrie-Werke AG (BERKA) – to correspond nominally to the stipulations of the Treaty of Versailles.

In 1928, Günther Quandt takes over the company. In the foreword of the anniversary publication to celebrate 50 years of the corporation, he writes »In this way, however, it was possible to provide the Führer at the point of his seizure of power with a factory, in which the production of weapons could be immediately resumed on a large scale«.

In 1936, the Treaty of Versailles is openly breached: The company bears the name »Deutsche Waffen- und Munitionsfabrik AG« (DWM) once again.

Countless slave laborers have to work on producing munitions during the Third Reich in inhumane conditions.

In 1949, Harald Quandt takes over as head of the board following the Second World War. The company now bears the name »Industrie-Werke Karlsruhe AG« (IWK).

From 1970, the company is known as »Industrie-Werke Karlsruhe Augsburg AG« (IWKA). From the initials of the acquired company »Keller und Knappich Augsburg«, IWKA is later renamed KUKA (2007).

Due to the relocation of production to the outskirts of Karlsruhe, the premises become an industrial wasteland in the 1970s.

The building as an industrial ruin, after it had been given up as a production site.

© KUKA AG

From 1981, the Hallenbau is used as the Kammertheater on the initiative of Reinhard Wonner and in 1983, it is discovered by Georg Schalla to realize his ideas and concepts.

The premises are initially used with the authorization of the various owners, then also without authorization, which can be taken as a campaign of cultural policy: countless exhibitions, concerts and performances are hosted here from now on.

In 1989, the ZKM is founded by the city of Karlsruhe and the state of Baden-Württemberg as a foundation under public law. The foundation is attributed to the idea of merging contemporary art with pioneering technologies.

A pioneering new building is planned as the domicile of the »elektronisches Bauhaus« (founding director Heinrich Klotz). As part of the redevelopment of the area south of the main railway station, an international architecture competition is advertised, with Rem Koolhaas being selected with his design for a 60m high cube with media facade. However, the project fails due to the cost.

The premises are initially used with the authorization of the various owners, then also without authorization, which can be taken as a campaign of cultural policy: countless exhibitions, concerts and performances are hosted here from now on.

In 1989, the ZKM is founded by the city of Karlsruhe and the state of Baden-Württemberg as a foundation under public law. The foundation is attributed to the idea of merging contemporary art with pioneering technologies.

A pioneering new building is planned as the domicile of the »elektronisches Bauhaus« (founding director Heinrich Klotz). As part of the redevelopment of the area south of the main railway station, an international architecture competition is advertised, with Rem Koolhaas being selected with his design for a 60m high cube with media facade. However, the project fails due to the cost.

As an alternative site, the historical Hallenbau A of the former Industriewerke Karlsruhe-Augsburg (IWKA) is selected.

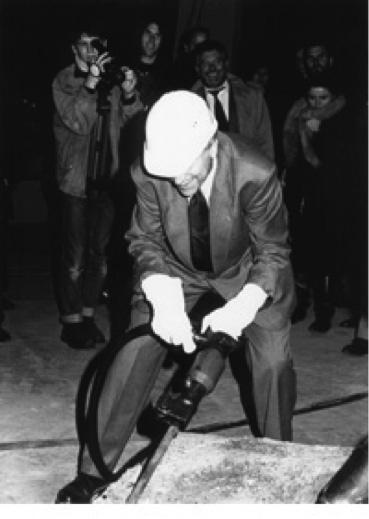

Heinrich Klotz, former director of the ZKM and founding director of the HfG, 1993 at the groundbreaking ceremony for the new house

© ZKM | Karlsruhe, photo: Evi Künstle

In 1993, the symbolic ground-breaking takes place. The renovation of the building, which is now listed, is undertaken by the Schweger + Partner architecture firm from Hamburg. The structure of the building is barely touched. Lightweight bridges and jetties for moving through the massive building, a blue box (today’s media theatre) and a high-tech cube in front of the building for the music and sound studio are added.

In 1997, the ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe is officially opened.

In 1997, the ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe is officially opened.