Martine Neddam: MyDesktopLife

In the Current of Time, History and Impressiveness

On Visual Poetry in the Film »This is Home«, by Martine Neddam

Bird song. Is it spring, perchance? A woman’s voice is faintly audible from somewhere in the off. Initially, one barely discerns a word since the speech rather resembles a whispering. It then becomes louder. A portrait of the actress Tilda Swinton playing Orlando from the eponymous film of 1993, flows across the picture. Texts such as »My Desktop« or »IS« hover above the surface, which, due to the menu bar situated at the upper edge of the screen, are unambiguously recognizable as the desktop image of a personal computer. At the same time, the backgrounds change, mostly comprised of photographs Martine Neddam took during her many journeys to India, such as to Orissa province, where tribes still live, much like in Africa. She also uses a small painting by Francis Alÿs with a boy who, dreaming – or is he dead - , lies prostrate in front of a machine gun. One hears »This is Home«. And, lasting 7:47 mins., this is the longest title of the group of works »MyDesktopLife« (2014). Or: »You are inside my head«. At some point the complete text types itself on the screen:

»Hello my computer, bonjour.

Every morning I greet you, I reboot you…

This is my life with you,

an animated life.

You are inside my head, I am in your memory; our living room is the desktop.

This is where we live together.

I look at the background pictures; I remember where I took them

Documents still laying around…

This is my life with you.

This is home.«

This film runs on the browser. And only on the browser. It is the reflection of essential experiences that anyone, in possession of a computer with graphic user interface uses, would share: it is a picture perpetual change. Files are added, shifted or deleted. Once again a new folder created and postponed. And then one not only opens programs, but windows in the files manager in order to look for files, to select, shift, open or delete them. Moments of concentration and reflection with moments of dispersal, since we are not created for the simultaneous processing of multiple tasks, even though there is hardly anyone who carries out a single task on the computer. Observe yourself: a media program is running currently, the email, browser, text processing, chat and Skype, all of which demand attention of various degrees of intensity. This is because these programs and systems are thus programmed: they vie with each other for users so as to in this way occupy themselves with them. The failed result of multitasking: as part of her most recent work, the artist starts out from her own experience of what users fundamentally experience when interacting with the computer. Working on the monitor, according to Martine Neddam, is comparable to an ongoing flowing filmic situation: “’MyDektopLife’ represents a flow of consciousness in various layers of fused images, texts, sounds and voices”, as the artist describes her own work. To describe it as a stream is no understatement. Daydreams and reflections on computer activities manifest themselves in a silent, irritating, poetic manner, and all prompted by the impressions evoked by the inner eye in times of small absences.

In »This is Home«, a film especially produced for ArtOnYourScreen (AOYS), desktop images combine with photographs, memories, text and automated translations, linked to ephemeral voices. Occasionally, unexpected pop-ups or signal tones disturb the observer of this inner film, before once again bearing him away with each current consisting of personal memories and saved data. In this way, various layers are combined with one another in vivid connection as filmic process: words, interpretive, explanatory sentence fragments about the act of memory, the computer, one’s home and the relationship between user and computer in pictures taken by the artist on her journeys, which, in turn, could count as more than blurred memories and which, in the form of photographs, affect and manifest a rigid immutability to which they do not actually correspond. This is because memories are fluid. Furthermore – and this, perhaps, is the paradox, they meet technical symbols that have similarly become contemporary history since yet another new version of the Mac OS operating system has been introduced to the market – Apple is the artist’s primary working platform. And, in principle, they reflect the control-less net-experience of »surfing« on the Internet, a cultural technology which, due to the omnipresence of mega-platforms such as Facebook or Google is no longer exercised. It is difficult to find precise adjectives for this hitherto unprecedented approach to thinking about the relationship between man and machine. It is precisely the extraordinary quality of this artistic concept of generating visual form which epitomizes this in a diffuse, open and melancholic manner. This aspect of the work is, as it were, the artist’s showroom in AOYS. However, a peek backstage is also offered.

About the Software

How does such a film arise? What kind of tool was used? A peek behind the scenes: the software that prints the result of the work with its own stamp, has long-since been a platitude. In his book “Software takes Command” (2013) Lev Manovich answers questions about this influence by way of important products in the industry. Accordingly, there is no shortage of analyses. And yet, as a rule, there are hardly any alternatives to this tool, which Manovich simply adopts and accepts as a given. The power of the market giants appears too big. Is Photoshop by Adobe really the non-plus ultra of image processing? Or is it not far more a cliché that the product name – doubtless cult-like and cool – functions for years now as a synonym for the manipulation of Jpegs, Tiffs of Gifs. To take a backward glance: At a time before we writers, photographers, gamers, hobbyists, fun programmers gave any thought to the computerized fulfillment of the desire for automization and manipulation and were still sitting before the Gabriele by Triumph-Adler, in front of board games such as Mensch-Ärgere-Dich-Nicht (similar to Ludo), or were muddling around with liquid fixer in darkened chambers, a system had been developed which operated according to quite a simple logic: for every task a small program. Roughly speaking, this is Unix’s motto. This toolbox philosophy is indebted to the user tools which, above all, smoothly carry out tasks in unified ways without a graphic user interface. Furthermore, in so-called Shell scripts one can combine programs and use them for repeating tasks. By contrast, there is a trend towards increasingly bigger program packages – especially evident in the graphics and multimedia sector – and such that it can only be interpreted as a trick collusion between the software and hardware industries: bigger programs require more powerful computers, and thus I also buy a new computer with each new upgrade. Furthermore, the built-in filters are standardized. One looks at the products, and the means with which they arose. The programmer’s stamp. Little wonder that software is always limited.

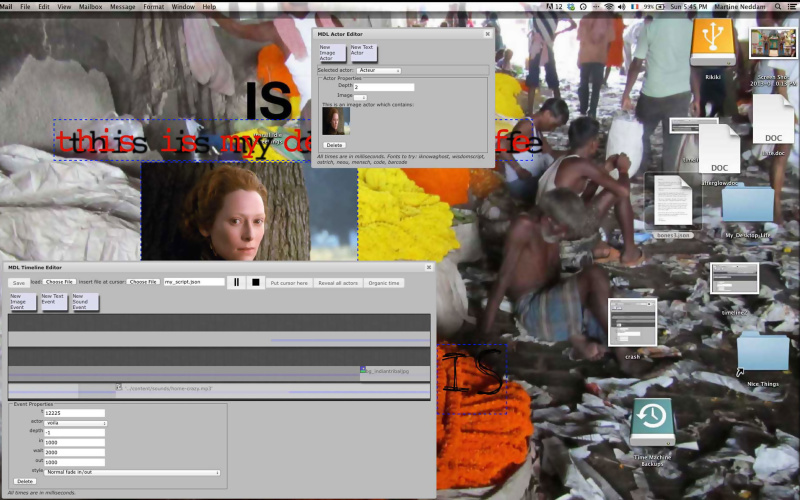

However, Martine Neddam was unsatisfied with this situation, and collaborated with the programmer James Hudson on her own software which, naturally, is also limited, no less in view of the contemporary area of usage. With Hudson, Neddam developed »MyDesktopLife« for her complex of works – an online tool based on open standards, and especially designed artistic requirements. It is comparable to video editing software. Contents can be added, directed and altered via a timeline. Thus, in the broadest possible sense, Neddam creates films through the permanently changing desktop of her computer. The artist is currently planning a complete content management system for artistic purposes.

| Author: | Matthias Kampann |