Harald Falckenberg: Gianfranco Baruchello

Back to

Introduction by Harald Falckenberg to the publication »Baruchello: Certain Ideas«, edited by Achille Bonito Oliva, Carla Subrizi, Dirk Luckow, Peter Weibel and Harald Falckenberg, published by Electra, Milan, in 2014.

__________________________________

It was one of Gianfranco Baruchello’s subversive and enigmatic »certain ideas« that prompted him, in October 1966, as the student protest movement was hotting up worldwide, to send the American government a proposal correctly addressed to »The Secretary of State for Defence. The Pentagon Washington 25, DC« with details of a Multipurpose Object. As pictured on the cover of this catalogue, this strange device is far too elegant for military usage: a kind of hand grenade or stylized mechanism for reloading a repeating weapon, offering a relaxing and useful exercise for soldiers in the field. The Pentagon assessed the proposal and responded, as expected, with the polite rejection letter from November 1966 that is reproduced on the back cover.

It is worth thinking about this work given such a prominent place by Baruchello, and to bear it in mind as a leitmotiv while studying the many-facetted, thoroughly researched catalogue. It was published in 2011 on the occasion of the retrospective entitled »Certe Idee« at Rome’s Galleria Nazionale D’Arte Moderna under the overall control of Achille Bonito Olivia and Baruchello’s wife, the art historian Carla Subrizi. With over 100 international solo shows and more than 300 group shows, the artist, writer, philosopher, psychologist, scientist, architect, archivist and director of the farming project Agricola Cornelia has written history.

When, three years after the Rome show, Deichtorhallen Hamburg / Sammlung Falckenberg under Dirk Luckow and the ZKM Centre for Art and Media in Karlsruhe under Peter Weibel decided to hold a comprehensive show of Baruchello’s oeuvre and to republish the 2011 catalogue in English, they did so in recognition of the artist’s global significance. Baruchello is among the key figures who in the 1960s and ‘70s, beginning in New York but also in Italy, France and Germany, declared war on the bourgeois culture of representative art and the commercial art business, calling for a critical, political and socially conscious art. For the broader public, although not for specialists, Baruchello has been largely forgotten, and the reason is easily identified: like few other artists, he stuck with his work for over 55 years, unwilling to enter into the proliferation of artistic currents from the late 1970s onwards.

And he was right, as we want to show with this publication – especially today. For a long time now, the conditions prevailing on the art market have been pointing to a re-feudalization of art under new rulers, and in political terms we are coming dangerously close to a new Cold War between the major powers over the world’s economic resources. Deichtorhallen Hamburg / Sammlung Falckenberg and the ZKM, Karlsruhe, have been addressing these issues for some time. In a series of joint exhibition projects including Paul Thek (2008), Bob Wilson (2010), Aby Warburg (Atlas, 2011, curated by Georges Didi-Huberman) and William S. Burroughs (2013), they have engaged with critical art and theory. These projects were preceded by retrospectives at Sammlung Falckenberg focussing on Vienna Actionist Otto Mühl (2005) and Peter Weibel (2006) who switched from the Vienna Group circle to the Actionists.

I first became aware of Gianfranco Baruchello while preparing the exhibition »Art and Politics. Erró, Fahlström, Köpcke, Lebel« at Sammlung Falckenberg in 2003. The close artistic ties linking Baruchello to Erró and Öyvind Fahlström are documented in the catalogue for the exhibition »Let’s mix all feelings together. Baruchello, Erró, Fahlström, Liebig« curated by Georg Bussmann and Armin Zweite in 1975. In 1966, Jean-Jacques Lebel and Peter Weibel participated in the famous »Destruction In Art Symposium« (DIAS), and from the early 1960s Baruchello took part in Lebel’s Libre Expression actions in Paris. Both participated actively, together with Erró and the psychoanalyst Félix Guattari, in the student revolt of May 1968. They were supported by Marcel Duchamp who exerted a key influence on the development of art in 1960s New York. Duchamp died after the revolt had been put down in the autumn of 1968. Robert Lebel, father of Jean-Jacques, had published the first edition of the legendary book Sur Marcel Duchamp in Paris in 1959. Baruchello met Duchamp in September 1962 in New York, leading to a close personal and intellectual relationship. Baruchello wrote several essay on Duchamp.

His artistic breakthrough came in October 1962 when, on the recommendation of the gallerist Ileana Sonnabend, he contributed to Pierre Restany’s exhibition at New York’s Sidney Janis Gallery that juxtaposed the artists of European New Realism – Fahlström also took part – with rising stars of the American Pop Art scene like Jim Dine, Robert Indiana, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, James Rosenquist, Andy Warhol and Tom Wesselmann. The show is considered as the birth of Pop Art.

Baruchello’s mother was a primary school teacher and collaborated with the magazine »School Rights«. His father was a lawyer, professor of business and industrial organisation, and manager of the General Fascist Confederation for Italian Industry. After his parents divorced, Baruchello stayed with his father. He studied law and became the manager of a company belonging to his father’s confederation. In 1959, at the age of 35, Baruchello decided to break with his past and become an artist. Not least due to the support he received from Duchamp, he quickly found his feet in New York and befriended many international artists. He settled his scores with the fascist past using the means of art, quietly and poetically, subtly enigmatic and without slogans or manifestos. This approach allowed him to maintain his Italian identity and not disfavour his origins.

The Italy of the 1960s and ‘70s was a stronghold of visual art, political literature and, along with France, of avant-garde film in Europe but eventually lost its momentum due to the rise of American art and the establishment of an international market, with Art Cologne (1967) and Art Basel (1969) as forerunners. Baruchello continued to largely work in Italy and refused to give up his convictions and art practice. On account of this attitude, his work – in spite of being featured no less than five times at the Venice Biennial (1972, 1988, 1990, 2004 and 2013) – never fully achieved the deserved international recognition. Punk, Neo-Expressionism, Transvanguardia, the Pictures Generation and the subsequent shift towards aggressively formulated political content (gender, post-colonialism, post-Fordism) were of no interest to Baruchello. With painting, photography, film, video, installation and performance, his metier is multimedia art. The motto coined by the art theorist Marshall McLuhan in 1967 still applies: “The medium is the message.”

The first works from 1959 deal with collages and décollages using objets trouvés and white-grounded paintings with lines, words and numbers, very much in the style of the time. In 1964, Baruchello began producing his meticulously painted objects with symbols and linguistic elements in the form of various layers of Plexiglas over aluminium-coated cardboard to achieve spatial effects. In the same year, these overlapping spatial effects led to the idea of his first and perhaps most important film, Verifica Incerta (uncertain verification; English title Disperse Exclamatory Phase), in which he randomly cut together clips from mainly American films. The film was screened in 1965 at the Guggenheim Museum in New York and many times since at international institutions.

A new journey began into imagination and reality, so immense that I wanted to encompass parallel language experiences such as cinema, television, photography, activities, installations, writing-collages, etc.

»Verifica Incerta« is the source for the catalogue title »Certe Idee/Certain Ideas«. It is a play on words that works equally well in Italian and English. “The impossible things are certain”, as Baruchello puts it, and this is precisely what does not interest him as an artist. Instead, he is concerned with the »uncertain things« that appear occasionally and by chance as possibilities that can be verified: »Certain Ideas«, then, are things and ideas that are not firmly defined, but discerned by the artist rather like a flaneur. Quite complicated, but both logical and enigmatic.

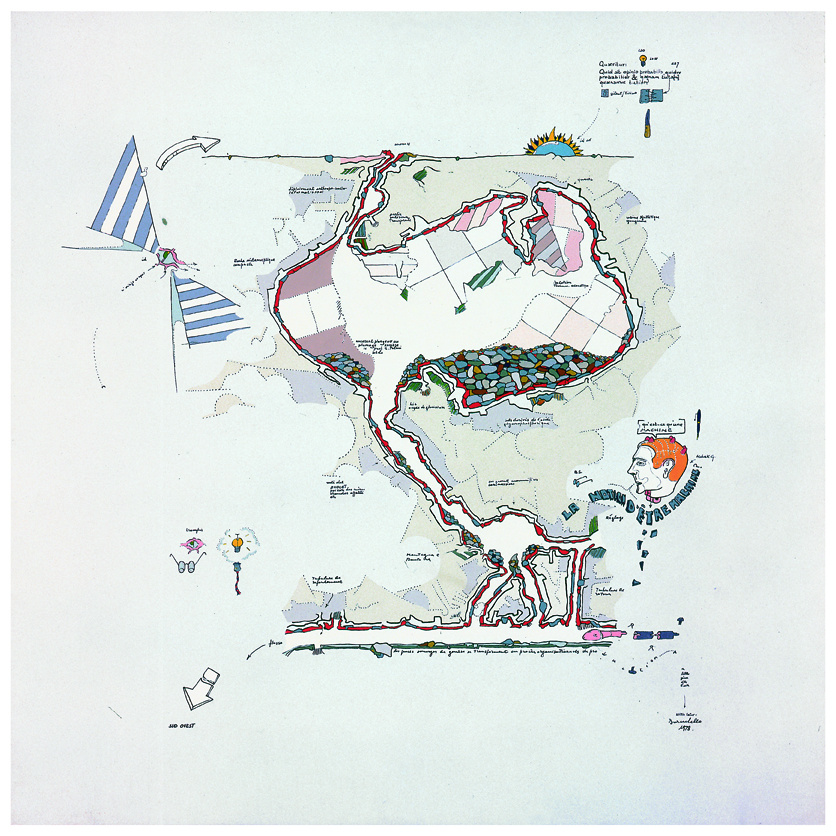

Following on from this, Baruchello applied his figures, objects, and elements of language directly onto medium- and large-format primed aluminium panels. These are the works that reached a broad audience and for which the artist is best known today. They, too, are not comprehensible in any conventional way and have no direct link with reality. Persons (perhaps better described as figures) and objects are broken down into elements; symbols and numbers stand alone, joined by brief quotations in various languages, words, and single letters. The artist deliberately offers no explanations. The reference points are psychological contexts and cognitive findings that associatively combine elements of the past and of reality in a succession of ways, expressing them through patterns and structures. Baruchello emphasizes: “The pictures are never arbitrary, they obey mysterious rules of arrangement that I cannot explain.” In the spirit of a participatory model, strategically positioned voids in the semantic structure leave space for the viewer’s own imaginings and conclusions. But the viewer should not hope for easy solutions. Instead, he must accept to enter the carefully encrypted labyrinthine world with little prospect of decoding.

It has shades of »Paradise Lost« when Baruchello frames the ruined remains of objects from bygone times and the breaking down of language and words into individual parts, as signs of the decline of shared cultural symbols and communications systems. “Let’s create stories and fairytales,” he says with an ironic undertone, “so as not to forget what they want us to forget.”

Let’s create stories and fairytales so as not to forget what they want us to forget.

He does not trust language and speech – the great seducers of all times – but rather objects: “For me, there is an element of mourning in objects, and you know that I love certain objects more than people.” This should not be misunderstood as a nostalgic pose. Baruchello is an analyst and a free thinker.

With his convictions, he is in accord with a whole generation of artists who, especially after the disasters of two world wars, began to systematically subvert the cultural values of the ruling political and economic classes that are orientated towards the Renaissance model of truth, beauty and goodness. Atonal music broke with conventional notions of harmony and rhythm; concrete poetry dissected language, words and rhyming schemes into their constituent parts; total theatre, performances and happenings saw the audience as an integral part of the staged events. In visual art, Dada, Surrealism and Fluxus stood for resistance to traditional definitions of art. Duchamp led the way here, provocatively defining his early-20th-century readymades as anti-art. In the early 1960s, he provided the decisive inspiration for the object art of minimalists like Donald Judd, Dan Flavin and John Chamberlain, and for Pop Art, as epitomized by Warhol’s Brillo boxes of 1964. These were works made using the ordinary means of industrial mass production. It was Duchamp who switched art from »high« to »low«. Today, these objects change hands for millions.

Baruchello eschewed this development. Although he did use the industrial products like Plexiglass and aluminium instead of conventional canvas, the minimalist paintings he applied to them (Baruchello: “We are no longer in the era of the Sistine Chapel”) were barely marketable. The same is true of his colleague Fahlström’s work, whose uncompromising anti-capitalist slogans were far away from the mindset of the New York art establishment. The isolation and dissolution of sentences and words practiced by Baruchello may be related to the ideas of concrete poetry, as found in Dadaist works, especially those of Kurt Schwitters. In the 1940s and ‘50s, William S. Burroughs came to the conclusion that the American capitalist society based on inclusion and exclusion could only be overcome by subverting its communications systems. “Language is a virus” is his famous dictum that was adopted in the 1970s by the French post-structuralists, most notably by Michel Foucault. Independently of this, in his 1969 novel »Die Verbesserung von Mitteleuropa« [The Improvement of Central Europe], the theorist of the Vienna Group Oswald Wiener asserted: “Language doesn’t help us escape from prison. It is our prison.” In Paris in the early 1960s, encouraged by his artist friend Brion Gysin, Burroughs developed the cut-up method. Taking his cue from Tristan Tzara’s 1920 treatise »How to make a Dadaist poem« as an expression of patterns of thought and representation free of logical constraints, Burroughs used an ordinary Stanley knife to cut up texts of his own as well as newspaper and magazine clippings, photographs, film stills and audio tapes, randomly assembling them into grid-based collages. These are the coordinates defining the historical and social context of Baruchello’s work and his political position. The genuine, distinctive quality of his artistic achievement is beyond doubt. Where others became loud and drastic, he remained silent.

According to Baruchello his art is inspired by books and pictures that provoke the mind and not the eye. But he is aware that this approach is barely accessible to typical recipients:

If I were to show my pictures to a bus driver, he would probably tell me ‘I don’t understand this kind of thing at all.’ That is sad, but not surprising. But when I show them to intellectuals I find that I can reach them to an even lesser degree.

And he draws the disillusioned conclusion: “The pictures are just another elitist commodity, destined to move through bourgeois communications systems and end up in the hands of a rich buyer.” (Galleria Schwarz, Milan, 1970)

These remarks were made in the historical context of the suppression of the May uprising in Paris. For several weeks, it seemed as if artists and students might join forces with the workers and the unions to create new standards for a fairer, open society. But targeted negotiations between the French government and the unions were all it took to quickly make the rebellion collapse. The disappointment was huge. In questions of power, the leverage exerted by art proved to be simply insufficient. The subsequent terrorist operations by the German »RAF« [Red Army Fraction] and the Italian »Brigate Rosse« [Red Brigades] took place without the artists.

Especially in Italy, but not only there, the early 1970s saw a hystericization of dealings with politically motivated radicals and criminal organizations, accompanied by massive use of law enforcement against suspects of all kinds. For Baruchello, this political crisis marked a caesura. It coincided with a reorientation of his personal life and his ongoing discontent with the art market. Baruchello was ready to wipe the slate and start afresh. In 1973, he moved into a country house on Via di Santa Cornelia on the outskirts of Rome, later purchasing ten hectares of surrounding land to farm. This was the birth of the Agricola Cornelia project.

Agricola Cornelia was not about dropping out. It was the logical consequence of Baruchello’s artistic ideas by other means. The artist understands his paintings as acts of devotion to objects – and to the related historical, cultural and psychological implications. All very theoretical. With »Agricola Cornelia«, he opened up a field that was down-to-earth in the true sense, allowing the artist to create something of his own beyond the discourses and petty jealousies of the art world. Baruchello practiced farming, but he never became a farmer. At no point did he ever stop acting as an artist. »L’Altra Casa«, a work from 1978/79 accompanied by a catalogue with a foreword by his friend the post-structuralist Jean-François Lyotard, is a significant example. »L’Altra Casa« was Baruchello’s attempt to be a kind of architect, designing rooms, baths, greenhouses and the positions of twelve beehives, thus breaking into a domain usually reserved for women.

For Baruchello, »Agricola Cornelia« is an open space bounded only by clouds and light, a kind of stage in the spirit of total theatre and total poetry. The organization reflects this approach and, in the best artistic spirit, it is run spontaneously and not on principles of economic efficiency. But with great commitment from all involved, everything worked just fine. The farming has long since been abandoned, as has the attempt to lay out and maintain gardens. Today the vast grassland areas in front of the house are kept more or less mown. There are paths to individual outdoor sculptures, dilapidated sheds with rusting agricultural equipment, and sparsely furnished outbuildings for students and artists in residence, as the author discovered during two visits. This is all wonderful, but it is far outshone by the main house. Together with Carla Subrizi, Baruchello has created an archive with countless books, historical newspaper clippings, documents of all kinds and works by the artist, a resource that in its quality and its unpretentious visitor access is truly unique.

In 1998, »Agricola Cornelia«, including significant portions of Baruchello’s oeuvre, was transferred into a self-financing foundation that does not rely on public subsidies. It is dedicated to young artists and scholars who wish to study the key developments in political and experimental art.