The Mnemosyne Atlas

The Hamburg cultural scientist Aby M. Warburg (1866–1929) was a pioneer of the modern study of art and visual culture. Before the First World War, he made his professional name as an expert in Florentine art through a comparatively small number of publications, which nevertheless consistently offered surprising insights and repeatedly led to sensational discoveries. What was utterly extraordinary, however, was the project to which he dedicated the final years of his life: the Mnemosyne Atlas, which has long remained a legend, even after its publication in 1993.

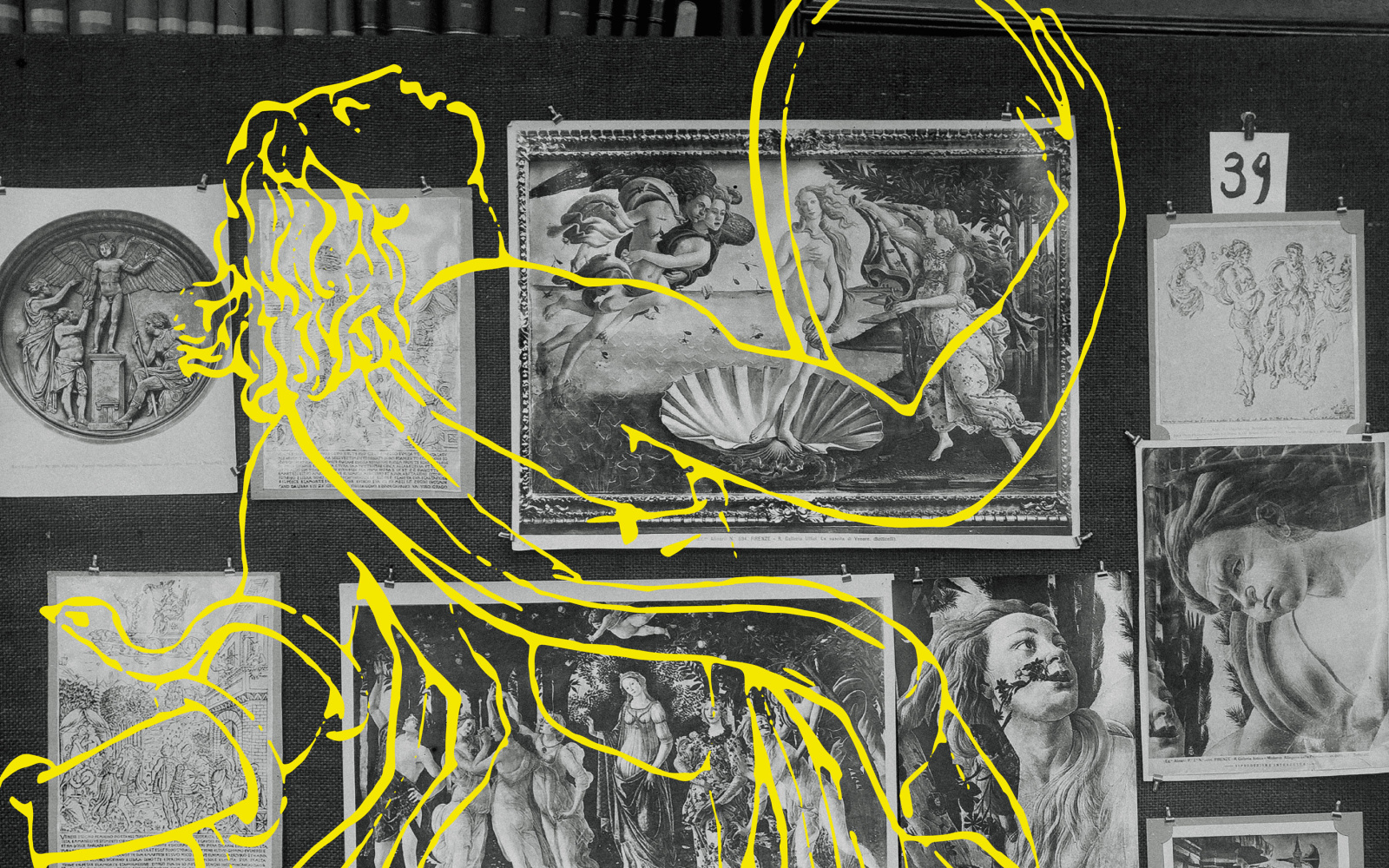

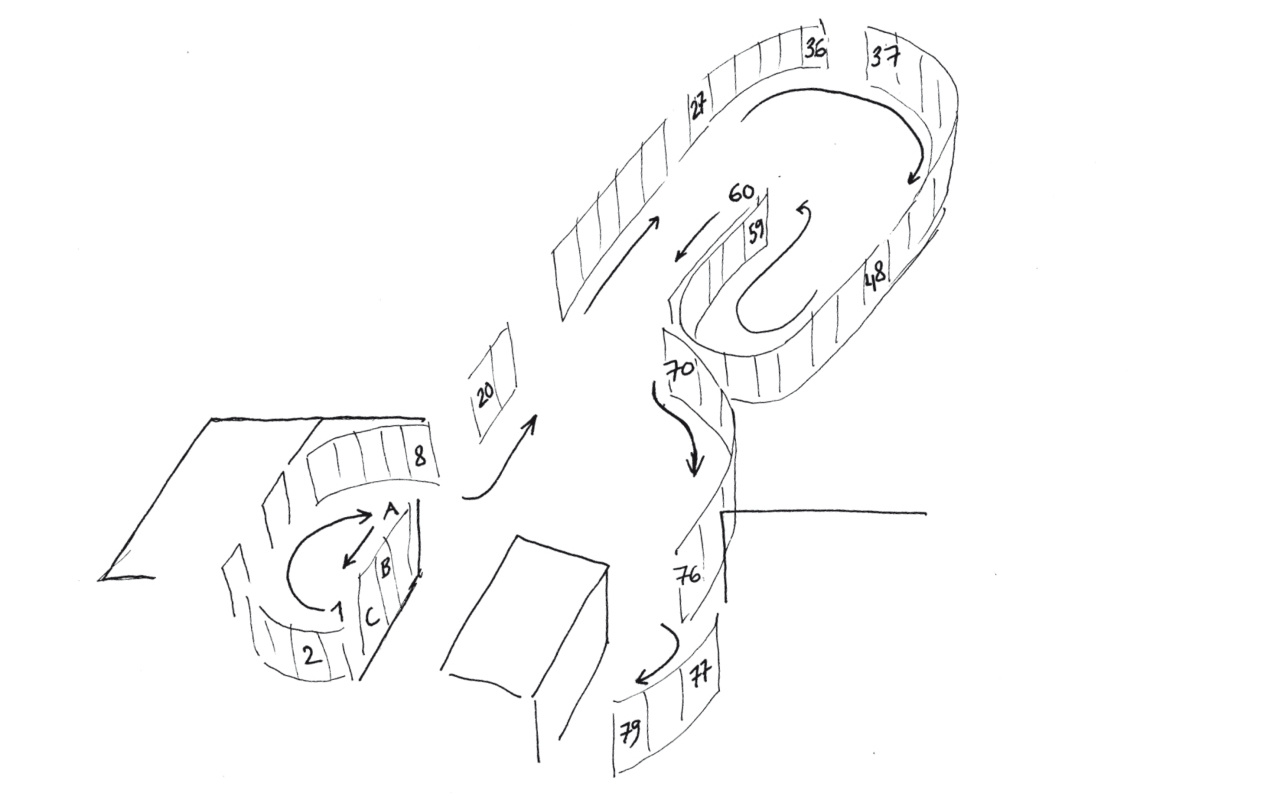

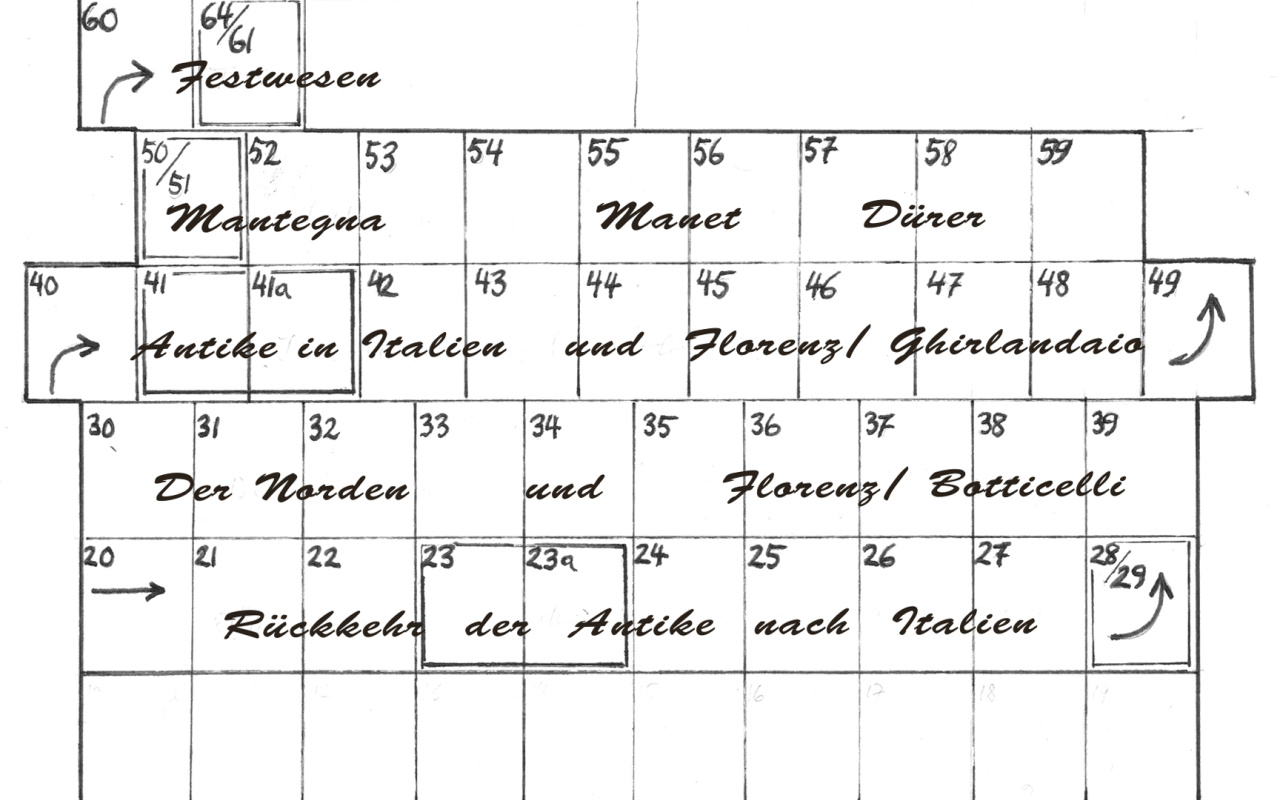

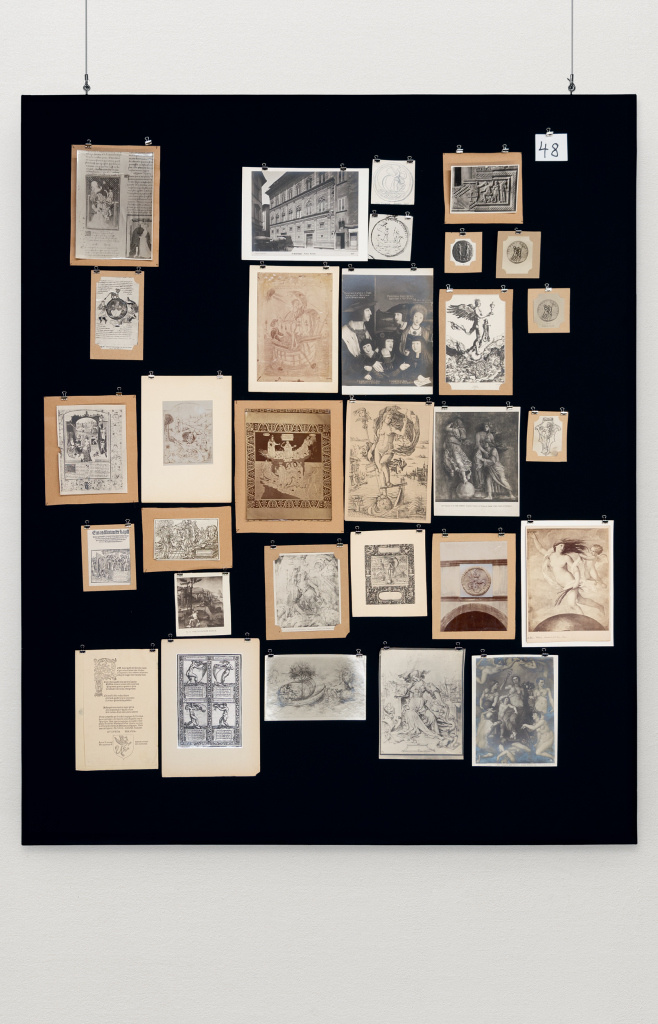

From 1924 to 1929, Warburg concentrated his entire body of knowledge in this collection of images, which ultimately spanned 63 panels and encompassed almost a thousand individual pieces. He predominantly used photographs, but also included illustrations from books or picture files, original graphics, and newspaper clippings. He even used postage stamps and promotional brochures. As a matter of course he made use of modern techniques of reproduction in order to develop an “instrument” of knowledge on this basis. To the present-day viewer, the work may well call to mind an Internet search engine’s flood of images, but Warburg’s panels are constructed with great deliberation and comprise a repository that condenses memory into complex constellations. He chose Mnemosyne, the Greek goddess of memory and mother of the muses, as the patron saint of his project.

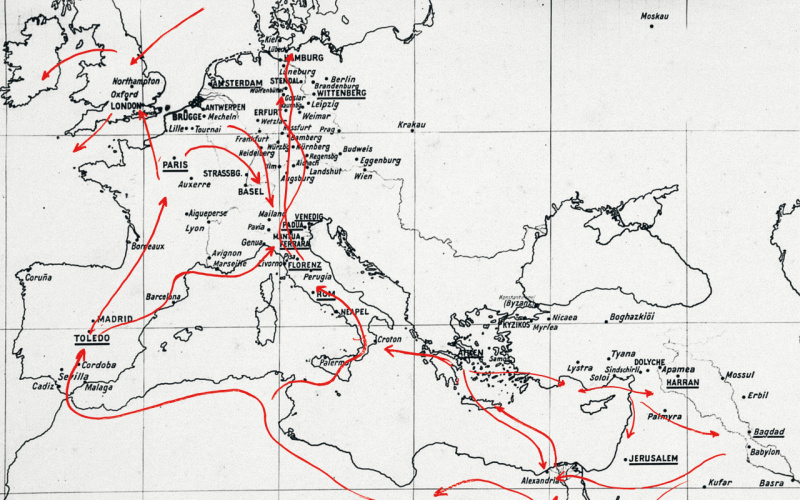

Warburg was concerned with the question of how the pictorial world of antiquity had come back into the European cultural sphere and led the medieval world into a new era – a classic problem with a very familiar solution: the Renaissance, the rebirth. The examples that are brought together on the panels of his “Bilderatlas” [atlas of images], however, have little to do with the great “masterpieces” and recognized “values.” They lead first and foremost into the Early Renaissance; they unfold a history of conflict, showing not the outcome, but rather a moment in which a struggle over the meaning of art was still taking place. Warburg never simply mapped out the dialogues and clashes of interest between artists, clients, philosophers, poets, and churches. The lines of conflict run through the very people involved – and through the works. It is little wonder, then, that the atlas also knows no boundaries within art. Painting, sculpture, graphic design, illuminated manuscripts, tapestries, wedding chests, playing cards, everyday objects, jewelry – in every area Warburg sought the clues that could help him.

________________________________

Text: Axel Heil, Margrit Brehm and Roberto Ohrt