In search of a dirty accomplice for a sustainable cohabitation and coexistence

A contribution by Francesca Romana Audretsch

There is one thing that connects all people, no matter what culture they are in: food. The culture of food offers a wide range of how we prepare and preserve our food. Even the eating itself is literally staged by the table culture with cutlery, crockery and decorations, thus creating a communal atmosphere.

Culture is in food, and food - at least temporarily - is in us. Food becomes a part of human beings themselves, as we absorb, process and digest it in our bodies. The cycle of food is accompanied by the excretion of our excrements. So it is not only the intake of food that connects all beings with each other, but also the excretion of indigestible food leftovers. 'Modern ideas' of hygiene and cleanliness determine our lives – whether at home, at work or when traveling. The daily use of the toilet is a matter of the unfiltered release of food into the earthly cycle. With a 'Flush!' the taboo subject of society is discharged. The fact that hands must be washed with warm water and, if necessary, disinfected is also reflected in the architecture of our living spaces since the 20th century, as pioneered by Louis Pasteur, a French chemist, biologist, physician and bacteriologist. Together with other scientists of his time he invented what we understand by hygiene today. However, our excrements do not disappear as quickly as the flushing of a toilet seems to demonstrate, but they remain in several organic layers of the earth: in ourselves and in the habitat surrounding us, the »critical zone«. Once flushed from our own household, the excrements end up in the sewerage system and are transported with the wastewater to municipal sewage treatment plants.

But what exactly happens in municipal sewage treatment plants?

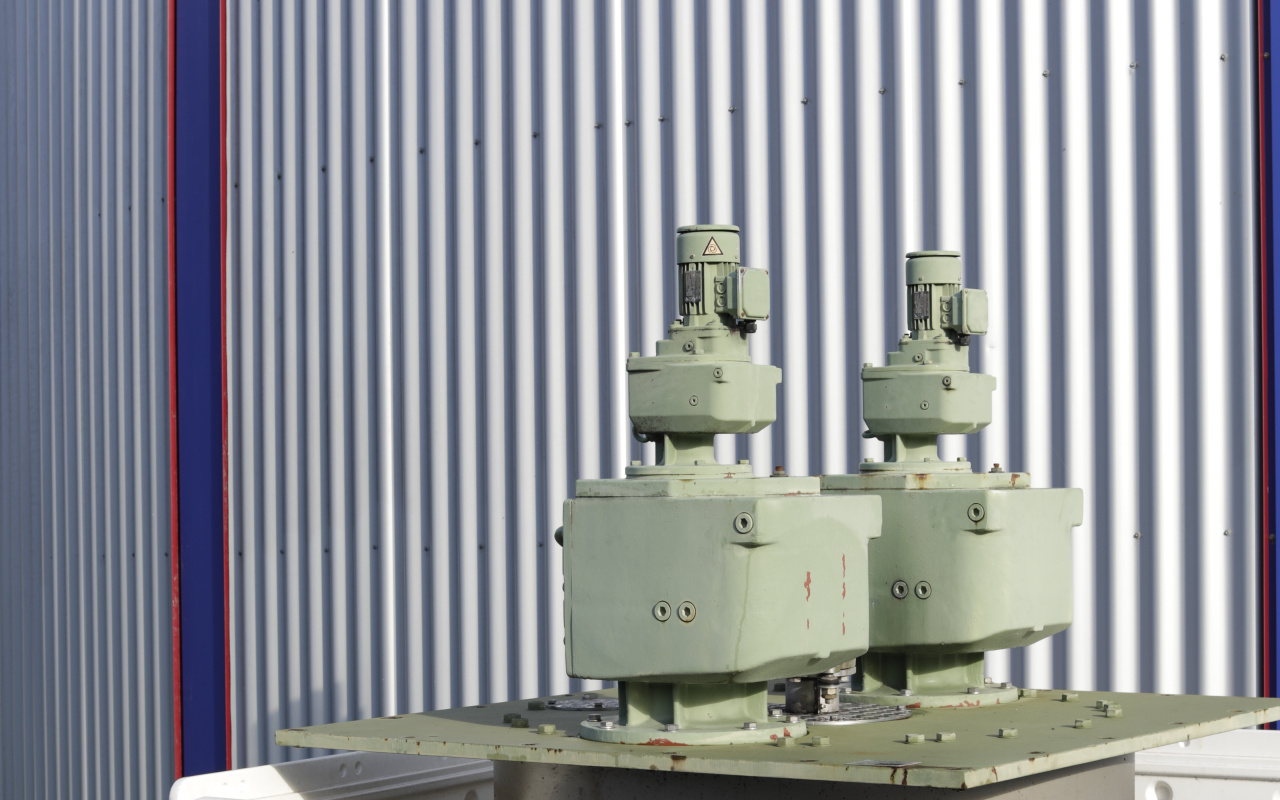

1,200 km long sewer pipes lead to the Karlsruhe sewage treatment plant in the Ettlingen district. Every second, 5,800 liters of wastewater arrive at the treatment plant through pipes as large as subway tunnels. The wastewater is a toxic broth consisting of 99 percent water. It contains not only toilet paper and cosmetic tissues, but also drug residues, microplastics, heavy metals and soil sediments. During heavy rainfall, extraneous water from construction sites can also be carried along. What exactly ends up in the wastewater and when this happens depends on various factors: Time of day, seasonality, the associated snowmelt or downpour, and periods of drought. Cultural events such as »Das Fest«, »KAMUNA« or trade fairs are major events that can be detected in wastewater. Once the wastewater has arrived at the sewage treatment plant, it passes several purification and filtration stages. The resulting sewage sludge consists of 27 percent dry substance and 73 percent water. Sewage sludge is a microcosm created by and for people. Its main task is to 'clean' human pollution. It therefore forms an important link between man, technology and nature. Sewage sludge has even made it into the realm of artistic positions, as Yvonne Volkart describes in her essay »Art and Ecology in the Age of the Technosphere«: In the occasion of Manifesta 11 in Zurich on the subject of work, the US artist Mike Bouchet placed 80 tonnes of sewage sludge in the White Cube of the Migros Museum. The Zurich Load', the title of this work, is the load of faeces that the inhabitants of the city of Zurich produce and flush down the sewers every day. (...) What was exhibited, however, was not, as might have been expected, a soft, formless mass, but neatly stacked cubes, arranged in a rectangle in the style of Minimal Art.«²

Stefan Knebel is operating manager of the incineration plant for sewage sludge in Karlsruhe. Not only is he proud of his 70 employees, who represent a rather small operation regarding the large populated area in which sewage is produced, but also proud of the microorganisms which live in and form the sewage itself. These microorganisms can also be referred to as non-human protagonists because they themselves contribute in various cleaning stages of the sewage. Incineration plants for sewage sludge are highly technical facilities which are designed to accelerate the natural process of the sewage to purify itself. But why though is sewage sludge relevant for our social system? As it occurs with various other systems none of them are questioned, as long as they function properly. The purification of sewage sludge is an important piece within the economy because it holds a resource which since May 2014 is regarded by the german Ministry of Environment as a »critical raw material«. More specifically, the resource Phosphor. Due to our nourishment we provide our body with phosphates. Phosphates are oxidized Phosphor and without it no life on earth neither humans and animals nor plants could live. As a mineral and an essential nutrient for all living beings no life could exist, prosper and develop. Phosphates anchor our bones, our DNA and our cell membranes.. These bounded elements direct our energy balance and therefore regulate our bodies.

Many industries use phosphates for numerous reasons:as water binding elements for meat products, as raising agent for bakery products, as flavor enhancer for soft drinks or as water softener for laundry detergent and dish soap. A recent usage of phosphates is related to the CO² emission-free electromobility in the automotive industry. The more people turn their backs on petroleum to buy a new electric car the quicker this raw mineral is spent. We should inherit the thought that humans and animals excrete phosphor which can be regained due to incineration plats for sewage sludge. Germany and France do not possess any natural resources of phosphor. Therefore the food supply industry of both countries is deeply dependent on phosphate imports from Africa. China and the USA use all their natural resources for their own production. The worldwide struggle for phosphor and the way it is being used, should be taken as another alarming example how the human species in this era of the so called ‚Anthropocene‘ is attacking the fundament which provides its own survival. Phosphor is a vital part of life and in a permant metabolic journey through our bodies and other organisms. It is necessary for every life form but it's abundance is limited to the terrestrial resources. So we have to choose how we want to form the future. Do we really want to perpetuate the past into the future? We as finite, mortal beings are confronted with the factor of time. The time of our own life and of others as well as the time of this planet. Therefore we experience various processes at the same time even if they are almost invisible. We are surrounded and permeated by light-, radio- and electromagnetic waves (WLAN) which escape our normal way of perception. In his 1913 speech »Humans and Earth«, Ludwig Klage plead to the »Free german youth« about the ecology of thinking. One can say that it was the first ecological manifest because it is about an act of creating a society in a way which is related to Donna Haraways eco-feministic thesis about an ecology of taking care. We have to vouch for all life on this planet not only for the human but also for the planetary.

So what makes sewage sludge a necessary actor in our coexistence?

Sewage sludge makes it possible to bridge habitual dualisms, spatial and temporal boundaries:it is both alive and dead at the same time, organic and technical, active and passive. It is disorderly and cross-border. It is populated by very different creatures. It smells unpleasant and we humans are disgusted by its deep brown, muddy texture. Sewage sludge is an accomplice in the attempt to draw attention to its vital collaborations with non-human life forms. In the sewage sludge it is not clear how the power to act is divided between human and non-human actors. Donna Haraway takes a counter position to the male defence and eradication of the non-human, as in the tradition of the hygienist Pasteur. She postulates: people should practice a non-pretentious cooperation with all those who are in the same earthly mess. For Haraway, cooperation and living means becoming entangled, intertwined and interlinked. In her research, she forms interfaces between feminist and political epistemology and the life sciences, and tries to broaden the human consciousness for a »non arrogant collaboration with all those in the muddle«. The aim is for people to playfully rethink the boundaries of everyday life and take responsibility for scientific and technological relations. Other actors and groups, such as the Spanish feminist initiative »Precarias a la Deriva«, which has been active for twenty years, emphasize not only how important it is to understand bodies as actors in themselves, but also put the ecology of care into a nutshell: »The negation of care is not far from the devaluation of the environment, from a society that destroys the environment, from a negation of the body«⁴.

The ecology of care is thus an appeal to society to stand up for the rights of the non-human. We must stand up for everything we are connected with. Our network of non-human and human actors is closely interwoven. The sewage sludge process is a phenomenon for thinking in cycles and a possible means to reach this state. There is therefore an extreme urgency at present to seek out and understand the nodal points of this interdependence. These nodes include the human microbiome as well as maritime and terrestrial habitats of various kinds. They all guarantee the survival of life. »Critical Zones« not only stands for our habitat or our earth's crust from a geographical and cartographic point of view, but also for »Contact Zones«. Which »Contact Zones« do we allow for a better living together? Who do we include? In other words: what demands must we make on our lives and the habitability of our living spaces?

With special thanks to Douglas Fullerton and Nis Petersen.

A contribution by Francesca Romana Audretsch.

¹ The Pasteurization of France, Bruno Latour, Harvard University Press

² Kunst, Wissenschaft, Natur Zur Ästhetik und Epistemologie der künstlerisch-wissenschaftlichen Naturbeobachtung, Yvonne Volkart, S.169

³ Anthropocene or Capitalocene?: Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism, Donna Haraway, S. 60

⁴ Ökologien der Sorge, Precarias a la Deriva, Transversal, S.42