- Event

MyCity, MySounds: Amble Skuse

Fri, May 17, 2019 8:00 pm CEST

- Location

- Cube

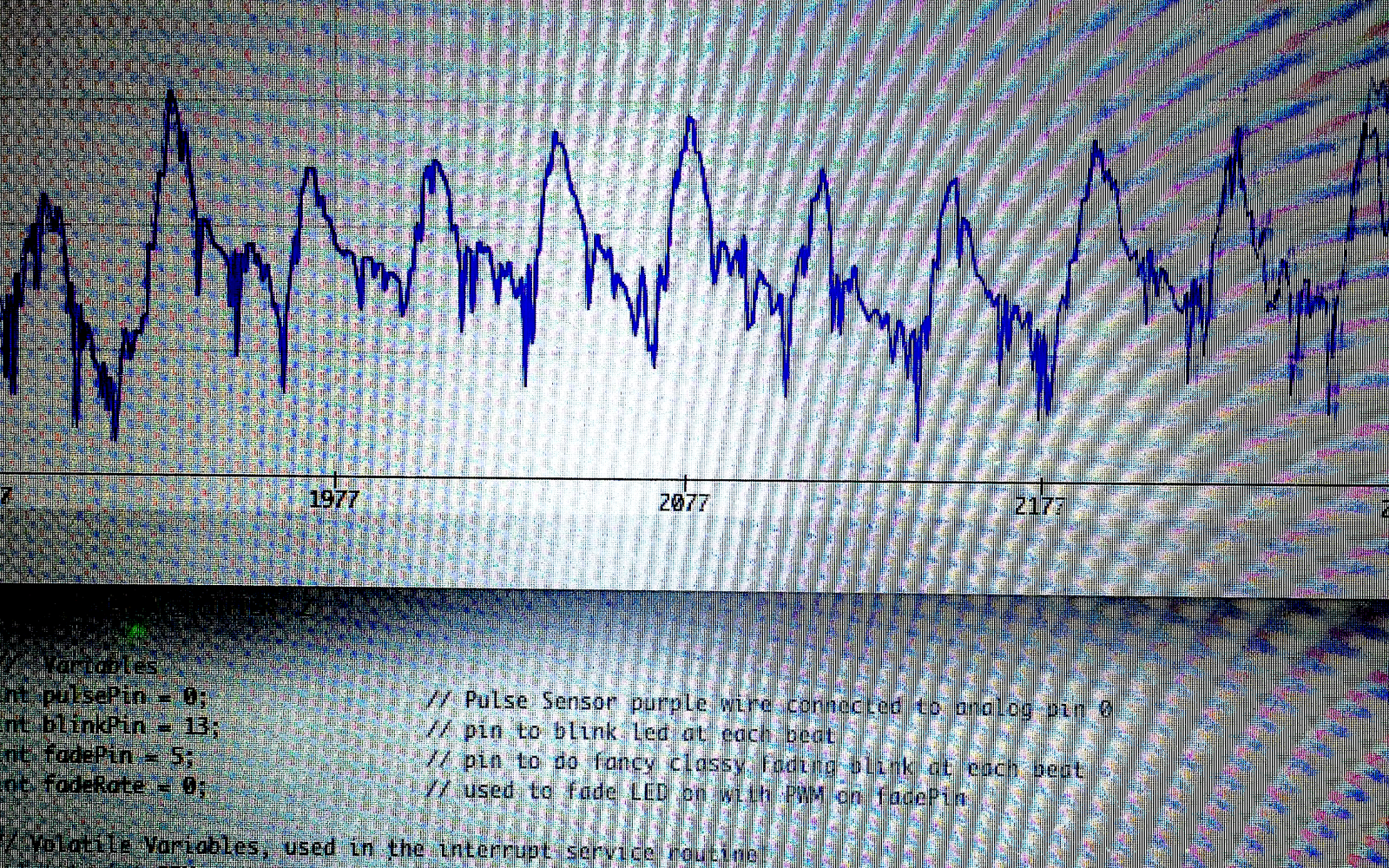

Using collected audio from the App »MyCity, MySounds«, Scottish composer and guest artist Amble Skuse creates a live soundscape performance, triggered by data from her own body, using bio sensors as cyborg controllers to interface between body and city.

What impact does a city have on a sick body? Amble Skuse's work artistically reflects the experience of how a disabled person experiences a big city. She is mapping and documenting the process of a disabled body interfacing with a new city via a series of body sensors (EEG & ECG), a sound recorder, video, photo stills and a location tracker.

Team

Yannick Hofmann (Artistic Direction)

Benjamin Miller (Sound Technician)

Hans Gass (Light- & Event Technician)

Sophie Caecilia Hesse (Organisation)

Organizing Organization / Institution

ZKM | Center for Art and Media

Begleitprogramm