Obituary Manfred P. Kage (1935–2019)

ZKM mourns the death of one of the most outstanding personalities in artistic and scientific microphotography. Herbert W. Franke has written the obituary.

There is no artist I have written about as often as Manfred Paul Kage. It has always given me great pleasure over many decades to report on his work: Paintings, animations, multimedia demonstrations.... It is the first time that it is bitter thoughts that accompany my writing this time: Manfred died recently. The only consolation is that the wealth of his scientific and artistic achievements is well preserved and documented in a wonderful setting: Weissenstein Castle in the Swabian Alb, where he lived and worked during the last decades.

BY HERBERT W. FRANKE

Manfred was born in 1935 in Delitzsch near Leipzig. There he looked into a microscope for the first time at the age of eight – a perspective that never left him. At the age of twelve, he fled from Delitzsch to Stuttgart, where he built his first own microscope from rubble [Trümmerteile] from Stuttgart. After his training as a chemical technician, in 1955, he was involved in development work for the chemical and optical industries. During microscopic examinations, he was struck by the aesthetic appeal of crystalline structures, which extended to the smallest areas.

Manfred P. Kage

»One day, while analyzing magnesium compounds, the scales fell from my eyes: I suddenly saw in a completely different way, detached from any scientific way of seeing. I saw in the crystalline processes, which I could play before my eyes, two-dimensional structures, rhythmic sequences and fascinating light-dark compositions.«

Urged to learn more, he gradually examined over 1600 inorganic and organic chemical substances for their aesthetic properties and recorded their views with photomicrographs. This intensified his latent affinity for art, and he began to study art and sought contact with artists. He got the opportunity to organize an exhibition in the studio of the painter Christa Möhring in Wiesbaden, which he called «Fotografie Informel«.

His aesthetic studies were successful, his presentations attracted interest. He was given the opportunity to be present with his visual works and multimedia concerts at many important events, including the World Exhibition in Osaka, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Biennale in Italy, the Olympic Games in Munich, the ZKM in Karlsruhe and several other institutions. And he has received many awards – for example, the Culture Prize of the German Society for Photography.

For his works of synthesis of science and art, he introduced and coined the expressions «Science Art« and »Modern Science Art« in the 1960s. When he founded an Institute for Scientific Photography and Cinematography in Winnenden in 1959, he not only accepted research commissions, but also found people interested in the »beautiful« photomicrographs that his clients needed for advertising purposes and calendars.

Kage's unique decisiveness is evidenced by an anecdote that is certainly a bit exaggerated, but just as surely has a kernel of truth. The story goes that one day Manfred heard that Zeiss had a depot with special equipment, and he was offered the chance to choose and purchase some of it. When Kage then stood in the cellar at Zeiss, he thought he had been transported to a treasure trove – he saw himself in front of an abundance of the most diverse high-quality optical devices. And when asked what he was interested in, he simply replied, »I can use all of this!« And he got it. To add to the story, it is probably necessary to mention that he was accommodated with the prices, and that he had repaired some defective equipment and adapted many a piece to progress.

With these pieces, supplemented by his inventions and later, over the decades, numerous newly acquired devices and optics that always corresponded to the technical standard, he was able to make true what he had set himself as a principle: to always offer the best technical quality for his industrial orders, scientific research as well as for artistic works. And beyond that, the images were captivating precisely because of their graphic appeal. Manfred worked intensively on the colors that can be produced in the microscope. In doing so, he never lost sight of the aesthetic aspect. Once, as we stood in front of his microscope, he told me that he sometimes felt like a leftover alchemist, forgotten by time. And that took him far back in time, to the footsteps of Ernst Haeckel: the images of small creatures that opened up to him were of unexpected beauty. This prompted him to train as a visual artist as well, in order to enhance the aesthetic quality of his micrographs of chemical substances and filigree biological structures.

Word later spread in industrial circles that his photographs were the sharpest of all photographers and could therefore be enlarged more. Testimony to this are countless brochures, magazines, books, calendars and even stamps.

When he started his own business in 1959, he received many commissions from advertising companies, publishing houses, television stations, museums, in association with research institutes, universities and other educational institutions.

And again, his work resulted in a connection with Ernst Haeckel. When Haeckel published his »Art Forms of Nature« in the form of drawings, there were some doubts whether these wonderful figures corresponded to reality or whether they were not partly Haeckel's fantasy. This suspicion has long since been disproved, but Manfred was able to provide the evidence even more convincingly.

He succeeded as a private person of a non-public institute the first invention and introduction of the color directly at the scanning electron microscope and the possession of such a device. Thus, Manfred produced images of the microplankton – of the unicellular radiolarians, diatoms and foraminifera – never before seen by anyone.

Manfred P. Kage at the ZKM

Manfred P. Kage is an artist of the collection and has been associated with the ZKM institution since its early days. His multimedia concert »Makro – Mikro« took place in the context of »MultiMediale 3« in 1993.

Likewise, he was represented in the exhibition »GLOBALE: Exo-Evolution« in 2015.

Opening: Exo-Evolution

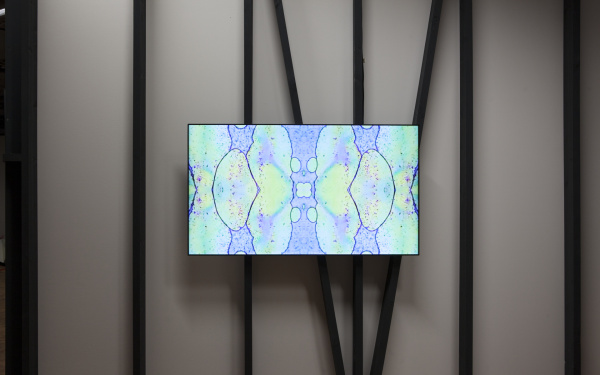

In his work in the field of video and multimedia art, he followed the principle of giving the viewers of his images the best possible idea of the dimensions of space and time. He achieved this with self-made projectors, such as his »audioscope«, with which music can be made visible in a special way, as well as film and photo recordings of complex microscopic structures. A special feature of his method is the possibility to control these instruments together with an eight-channel light organ he developed, as if with a piano keyboard. Such »Optical Concerts« are now presented by K4i (family artist collective; Christina, Ninja-Nadine and Oliver Kage) as medial, abstract light spaces, on domed roofs, on architecturally interesting buildings or in natural surroundings – usually together with live music by various instrumentalists.

Manfred's original idea of producing the optical effects live and in real time, like a kind of keyboard, is still today – together with Manfred's historical effects – the central characteristic of his family as his successors.

The remarkable images that resulted from his experiments were recognized by the well-known artist group ZERO and led to joint exhibitions and demonstrations. Manfred was one of the first members of this group, within which he brought to the public the previously described groundbreaking idea for the realization of the »Optical Concert«. These activities – together with other of his ideas – have contributed to the fact that today he is regarded as one of the pioneers of multimedia art.

These activities express another field of Manfred Kage's interests: music. In the early 1970s, Manfred became friends with two experimental musicians whom he had met in connection with activities at the Institut für leichte Flächentragwerke in Stuttgart, founded by the architect Frei Otto. There, Manfred worked for 20 years in two special research areas. Together with the two musicians, he presented a large multimedia concert in Stuttgart in 1970.

When the members of this community of musicians decided to look for a place where they could meet and work together, Manfred took on the task of searching for it in the Swabian region. And when he found something useful and at the same time wonderfully suitable, namely the idyllic old Weissenstein Castle, the musicians had scattered all over the world and were no longer interested. That's when Manfred Kage decided to purchase the property himself and enter into the financial terms that entailed many years of financial commitment – a life's work. He also took over the renovation, set up his Institute for Scientific Photography in the house and later, together with his family, converted part of the building into a museum. Incidentally, he had found remnants of the showpieces of a pharmacist's museum in the castle, which he included as a historical part of his museum collection.

In the end, it was Manfred's artistic work, which had already received much attention at the time, and in particular a world-exclusive publication, »Moonstone as never before« in the magazine »Bild der Zeit«, through which he succeeded in convincing the previous owner of the castle of his person in such a way that he gladly accepted Manfred as the buyer and future owner of the castle.

After moving into the castle, Kage continued his work. He provided prospective buyers with enlargements of high-resolution images, but he also engaged in the development of new optical methods and invented optical devices. He included cinematography in his field of work, participated in the work with the U-matic standard, and through his moving images came into contact with Salvador Dalí, who after successes with two of his films had ideas for another film work, which he called 'Journey to High Mongolia'. The images, which were then shown on television, came from Weissenstein Castle: they were journeys over colorful micro-landscapes that could be interpreted as aerial shots. Dalí added special elements to some of Manfred's microphotographic pictorial works, which he had discovered in his mind's eye in scratches and hatchings of the surface of a ballpoint pen. The artist was highly satisfied; after the work was done, he told Manfred, »This is even more fantastic than I could have dreamed.« At the end of the film, Manfred is introduced as the »Wizard of Weissenstein« who created the micro-scale special effects for this film.

In 1992/93, a teaching position as a visiting professor at the Staatliche Hochschule für Gestaltung Karlsruhe (HfG) followed. Manfred developed his own course of studies in the field of media art and, in this context, gave two large multimedia concerts in Karlsruhe (inauguration of the HfG Karlsruhe and »MultiMediale 3« at the ZKM: »Makrokosmos-Mesokosmos-Mikrokosmos«).

A few years later, in 2007, Kage and his wife Christina applied his method to a very different unusual project: »The Crystal Planet«. I had written the script as a model for a puppet play – already in view of a collaboration with Manfred, who contributed multimedia-generated scenery. It was premiered at the Marionetten-Theater in Bad Tölz and is still performed from time to time – with the wonderful micro-trick sequences by Manfred and Christina Kage.

By the way, there is also an idea developed by Manfred, which year after year is connected with the ceremonial opening of one of the largest computer art congresses in the world, which takes place every autumn. When the first Ars Electronicawas prepared in the capital of Upper Austria, I recommended for the opening evening his 'Music for a Landscape', an open-air concert with light effects, which Manfred had premiered in the valley of Weißenstein a few years before. This suggestion was accepted. For this performance, he collaborated with Walter Haupt, who was then director of the experimental stage of the Munich State Opera.

This open-air performance in Linz was given the name »Klangwolke« (Cloud of Sound) and became the first program item of Ars Electronica in each case – a signal for artists turned towards modernity, but also a point of attraction for the population of Linz – and far beyond. Even at the first performance, more listeners and spectators had gathered than had ever gathered in Linz. I remember it well: it was a mild September evening in 1979 in Linz near the city center above the Danube. And year after year, new electronic instruments come into play, creating astonishing light effects. It is not only the artists who travel to Linz who are moved by the impressions conveyed, but also parts of the population who otherwise have little interest in art. I see the Linz »Klangwolk«e as Manfred's legacy.

This only mentions a few select performances by the artist who was able to transform the microcosm into a moving art space – one could continue the list for a long time. All this is not enough to make my sadness about the death of Manfred Kage more bearable; but I take it as a sign that his artistic works are still alive.

According to Manfred's explicit wishes, his artistic and scientific life's work will be continued by his relatives: Christina, Ninja and Oliver. For years they worked closely with him. In the beginning they supported him, later they created together, they were involved in his photographic and cinematographic works and in the public performances. Today, they work with the help of unique instruments invented by Manfred, for example, to endow his images with magnificent plays of color or with novel artistic effects. It is the legacy that Manfred left to his family; and the residents of Weissenstein Castle have resolved to continue to publicize it, to develop it further and to dedicate some novel demonstrations to Manfred's memory. Thus, in the future, the admirers of his creative power will be able to enjoy his legacy.

One more thing is worth mentioning, and that is the Weissenstein Castle: a monument to Manfred, which is taken care of with great care by the Kage family: Christina, Ninja and Oliver. Already in recent years, Manfred confidently placed the management of his Institute for Scientific Photography and the family business in the hands of his family. The institute will continue to be run by them in the spirit of its founder. In the future, more new works of art will be created there and new methods will be developed – entirely in the spirit of Manfred. Moreover, in Weissenstein Castle, with the museum now called »KAGE'S MIKROVERSUM«, virtually everything Manfred created in his busy life will remain spread out before posterity: Pictures, films and animations, including the art collection and the picture archive, the historical collection of equipment, the material of the works – testimonies to the quality that the picture magician Manfred Kage achieved with his instruments.

Everywhere in the rooms and corridors of the castle one can admire his creations, and if one accidentally enters his old workroom – the light extinguished, the curtain drawn – then one or the other visitor will not notice for seconds that it is the old laboratory coat lying there spread over the backrest, but may have the impression that it is the master himself sitting bent over the unusually large microscope – his eye on the eyepiece, his hands on the adjusting wheels. And that his creative energy is far from extinguished. And he is even right about that.