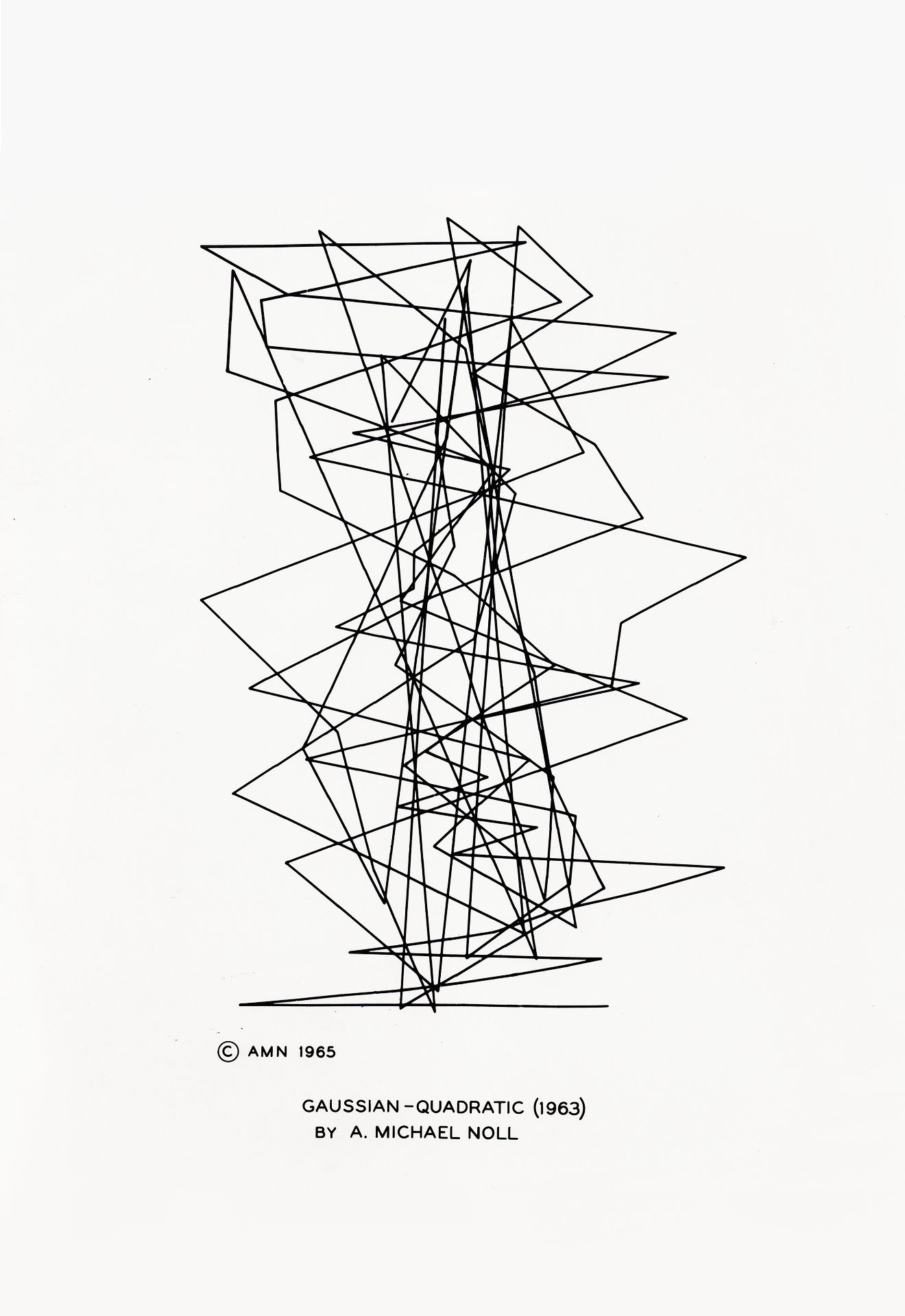

A. Michael Noll

Gaussian-Quadratic

1963

- Artist / Artist group

- A. Michael Noll

- Title

- Gaussian-Quadratic

- Year

- 1963

- Category

- Computer-generated

- Photography

- Format

- Black-and-white Photography

- Material / Technique

- computer-generated graphic; black and white photographic print from 16 mm film, production: IBM 7094, Stromberg-Carlson SC4020 Microfilm Printer, programming language: FORTRAN

- Dimensions / Duration

- 28 x 22,1 cm

- Collection

- ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe

- Description

- "During the summer of 1962, while I was employed as a Member of the Technical Staff at Bell Telephone Laboratories, Inc. (Bell Labs) in Murray Hill, NJ, I programmed the IBM 7090 mainframe computer in Fortran to produce images that I considered to be digital computer art. Mathematical equations were combined with calculated random numbers to create the images – what is today known as algorithmic or generative computer art. I documented my patterns in a Bell Labs Technical Memorandum dated August 28, 1962. [1] The computer would calculate and generate many different versions of the patterns – I could then choose the ones I liked. One algorithm calculated Gaussian random numbers for the X-axis and used a quadratic equation for the Y-axis. I particularly liked a version created in 1963, possibly because the pattern inadvertently resembled Cubist art, reminding me of Picasso’s Ma Jolie, which was at the Museum of Modern Art. I called my work Gaussian-Quadratic. I am told that today some computer artists and historians consider this image “iconic” and instantly recognizable. Ma Jolie and Gaussian-Quadratic are shown adjacent in my 1970 published paper, "Art ex Machina". [2] The maximum plotter coordinate was 1023. When the vertical Y-axis numbers exceeded that maximum, they were folded modulo 1024. This created a downward effect, as the coordinates were then built back vertically. It was not planned, but was a result of the binary mathematics used for the microfilm plotter. It added to the Cubist appearance of Gaussian-Quadratic. My management at Bell Labs did not want me calling the works “art”; instead, I referred to them as “patterns.” One reason, I discovered decades later, was that AT&T (which supported half of Bell Labs) objected to work in music and art at Bell Labs. Some at Bell Labs simply believed that what I had programmed was not “art” – that a work to be considered “art” had to be made by an “artist” and shown in a museum or gallery. The computer-generated works were made on 35mm microfilm of the cathode ray tube (CRT) of the Stromberg Carlson SC-4020 microfilm printer-plotter. The 35mm negative could then be printed on large sheets of paper or used to make photographic prints, and even poster enlargements. An enlarged positive and negative were shown at the Howard Wise Gallery show in 1965. [3] The drafting department at Bell Labs labeled one print with its name and date, and glossy print copies were made. Small 8-by-11 inch photo prints are in museums, some signed (but not numbered). The paper prints were over 14 inches high. Colleagues would come to my office to get a copy. I had felt-tip markers in different colors and would ask them for their favorite colors, and then use the markers to trace the lines on Gaussian-Quadratic. They left with their own personal computer art, which they would hang with a magnet on the metal wall of their office. I had one of the hand-colored paper prints framed and donated it to a museum years ago. It was dated 6-8-1963, with my personal logo formed from my initials (AMN). I doubt any other paper copies survive today. I took a 35mm negative of Gaussian-Quadratic to the photography department at Bell Labs (probably around 1963, or so) to have an enlargement made. When the negative was placed in the enlarger, it slipped, creating a double image. I liked the effect and had a print made. I programmed three portions of Gaussian-Quadratic to be used for transparent red-green-blue color separations. I took the transparencies to the photography department to make a combined final, but the color final was blurry with dark splotches. It looked interesting, though. Large mounted prints of Gaussian-Quadratic were shown in the Howard Wise Gallery show in April 1965. A positive (black lines on white) and a negative (white lines on black) were displayed. Later that year, the versions of Gaussian-Quadratic shown at the Wise show were exhibited at the Fall Joint Computer Conference in Las Vegas, [4] along with analogue computer art by Maughan Mason. [5] After the Howard Wise show, a lawyer at Bell Labs suggested that I attempt to register the copyright of Gaussian-Quadratic at the Copyright Office at the Library of Congress. Although the work was created in 1963, the copyright notice on it was dated 1965, when it was first shown (published) publicly. My letter to the Copyright Office mentioned that it was computer art. The office replied that a work by a computer or machine could not be registered – only works by humans. I replied that a computer program combining mathematics with randomness created it. The office replied that randomness could not be registered. I explained that the “randomness” was also calculated by a program and only appeared random to humans. It was finally then accepted and registered – perhaps the first piece of digital computer art to be registered. A print of Gaussian-Quadratic was shown at the 1968 exhibition Cybernetic Serendipity, organized by Jasia Reichardt at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. [6] © A. Michael Noll: The Story of Gaussian-Quadratic, November 17, 2025 [1] A. Michael Noll, “Patterns by 7090,” Technical Memorandum TM-1234-14 (Bell Telephone Laboratories, Inc.), August 28, 1962.[2] A. Michael Noll, “Art ex Machina,” IEEE Student Journal, Vol. 8, No. 4, (September 1970), pp. 10-14.[3] A. Michael Noll, “The Howard Wise Gallery Show (1965): A 50th-Anniversary Memoir,” LEONARDO, Vol. 49, No. 3 (June 2016), pp. 232-239.[4] Frieder Nake, “Georg Nees & Harold Cohen: Re:tracing the origins of digital media,” media/rep/ (2019), p. 36 [https://mediarep.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/f7017d56-9284-49d2-852a…]. [5] http://dada.compart-bremen.de/item/agent/316 [6] Jasia Reichardt, “Cybernetic Serendipity: the computer and the arts,” Studio International (Special Issue), July 1968.

Author

A. Michael

Noll