Edgar Reitz: Gideon Bachmann, the »Vasari of film«

Film-maker and film critic Gideon Bachmann has died in Karlsruhe at the age of 89. His friend Edgar Reitz remembered his first encounter with him at the International Short Film Festival in Oberhausen. This text was written for the “Film Art on Air” Gideon Bachmann’s Interviews with Cinema Personalities 1955-1997 exhibition at the ZKM.

I first encountered Gideon Bachmann at the International Short Film Festival in Oberhausen. If I remember correctly, it was 1961 in the year before the Oberhausen Manifesto, which went down in film history. So, 55 years ago! We were young and inexperienced and were presenting our early short films with the expression of a desperate search for recognition. Gideon became a legendary figure in our perception because he came from the great international world of film to us, knew every celebrity between Hollywood and CineCitta, spoke all languages and sat at all tables. Already back then, it was an honour for us to be noticed by Gideon.

Later, when I had some successes of my own to show and was allowed to appear at the festivals with my films, Gideon was the ever-present personality, always interested, always with the air of friendship. If you walked through the festival scene in Cannes or Vienna by Gideon’s side, he would introduce you to countless people. It was always the greats, the filmmakers, producers, film scholars, authors or actors, who Gideon introduced you to. He was connected with them all in an intimate friendship, everyone was his friend, and Gideon spoke their languages fluently. English, Italian, French and Hebrew – it was incredible!

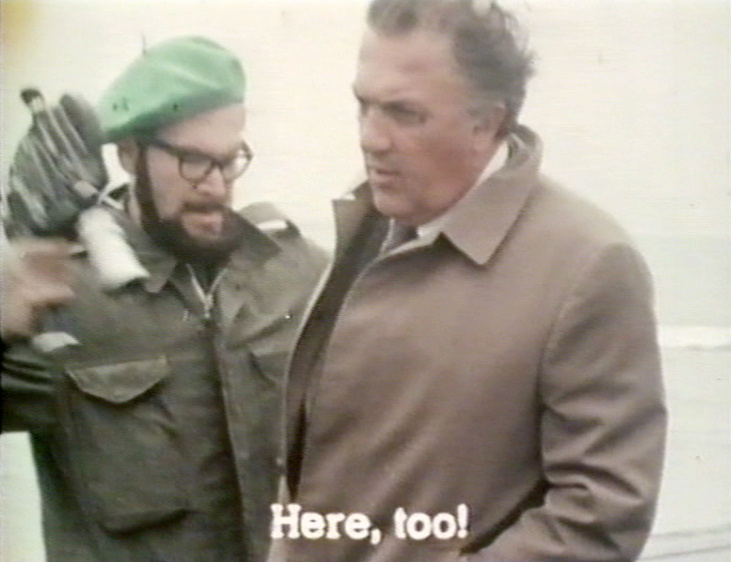

He once said to me that you should not be deceived by his accentless German, because there were lots of words that he didn’t know. But no one noticed this, because he had such a rare ear which tapped into pronunciation and tone right through to rare dialect colourations and enabled him to imitate them. Of course, this talent must have been one of the secrets of his tremendous communication skills. It was no wonder that Gideon became a type of “Vasari of film” with this ear and this sensitivity to language. When I think of those years, in which Gideon appeared at every film festival in the world and made his voice recordings everywhere, I see before me this strange image of a fisherman, who is casting his fishing rod. Gideon had actually built an absurd device, which he wore around his neck and which was connected with an expansive microphone boom which he had attached to his back. This allowed him to get his microphone into direct proximity of artists who interested him, over the crowds and the jostling journalists. Gideon eavesdropped on them at close range without falling into the thick of everyday journalism.

Gideon was always a friend. He achieved this through his limitless enthusiasm and his never-ending interest in people and their thoughts. We had many inspiring conversations about the question of what man’s strongest social driver is. Gideon recognised and formulated this desire for solidarity. Everyone, he explained to me, fears nothing more than being alone, than the feeling of not belonging to someone. Most biographies can be explained by this social desire, but also most conflicts and even wars, when it comes to different affiliations getting in each other’s way. Belonging is a risk and a dream at the same time. My preoccupation with the subject of home also grew from these discussions with Gideon.

It was 1994 when I met Gideon in a completely and utterly desolate state in Berlin at the Festival. His wife, photographer Deborah Beer, had died in Rome after a terrible illness, and Gideon was so deeply wounded in his soul that I had to fear he would not survive the loss. It was the year, in which I thought about founding the Institute at the HFG Karlsruhe. I asked Gideon to come to Karlsruhe and establish a centre for auteur films in Karlsruhe with me and Lothar Spree. It was a comforting experience that Gideon was revived through this task. I will never forget his expressions about the love, which he felt for Deborah all the more intensely as time went by and as he became more stable in his work again.

There are many stories that I could tell about Gideon from these years, stories of shared journeys to the officials of the European authorities in Brussels or Strasbourg, stories of encounters with rude children of the 68 generation, stories of visits to Bernardo Bertolucci in Rome. Along with his obsessions, his aversion to mechanical sounds and jumpiness and his affectations with his sensationally optimised luggage on airplanes. Gideon Bachmann is an unmistakable character, a person who has made an impact on thousands of places in the world and whose voice one can identify from thousands of voices. One heard repeatedly that he resisted time like no other. He was often the youngest among those present, despite his higher age.«

Edgar Reitz is a central figure of auteur film from the 1980s. Reitz achieved his greatest success with his almost 60-hour film cycle “Heimat” [Home]. He was the Professor of Film at the Karlsruhe University of Arts and Design (HfG).