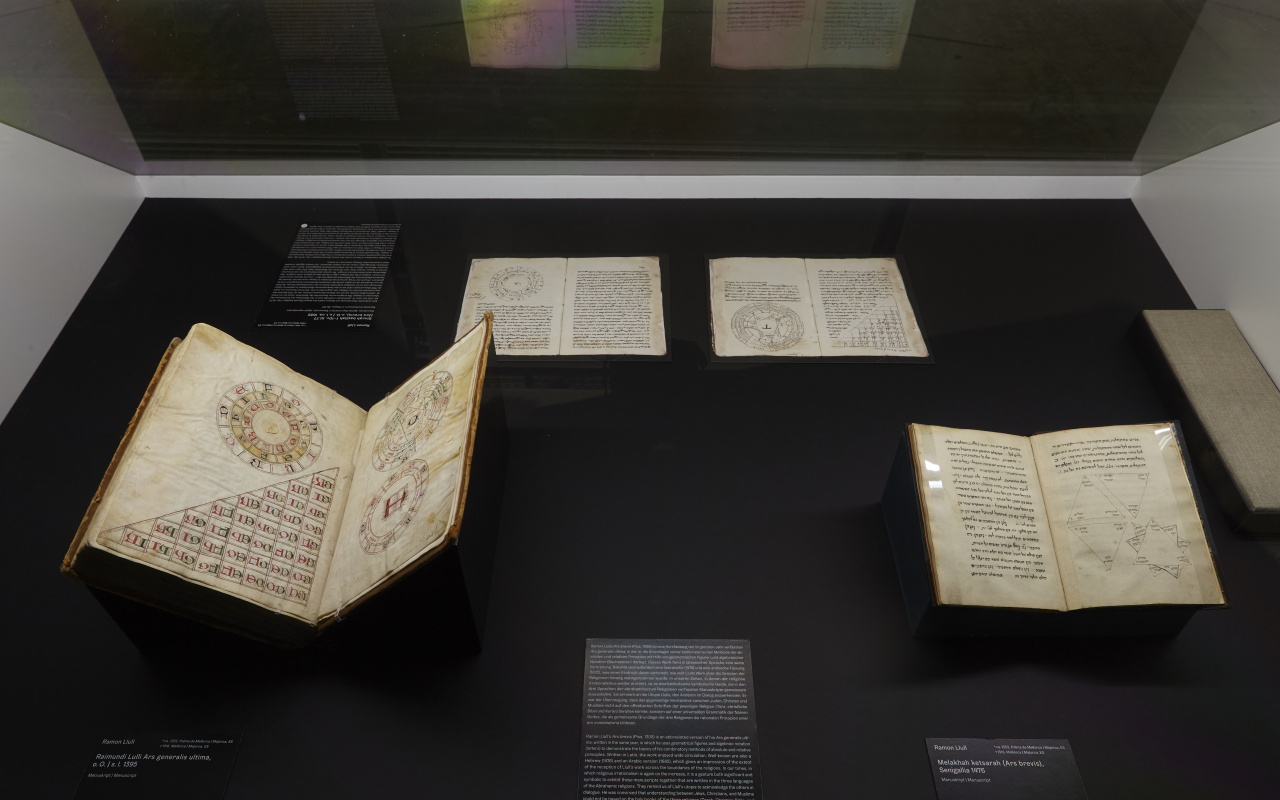

Exhibition view

DIA-LOGOS. Ramon Llull and the ars combinatoria

The »Breviculum ex artibus Raimundi Lulli electum« is the best known manuscript about Ramon Llull. It contains the shortest of three compilations of his basic ideas, and was written by his pupil Thomas Le Myésier (? – 1336), who presented it to Joan of Burgundy, Queen of France. The Breviculum is particularly known for its twelve large-sized miniatures depicting scenes from the life of Ramon Llull. As this illustrated manuscript must have been produced shortly after Llull’s death under the close supervision of his pupil Le Myésier in northern France, it is reasonable to assume that the depictions of Llull are fair likenesses. This makes the images very valuable for lifelike portraits were a rarity in medieval times.

The manuscript itself has an eventful history. To begin with it was in Paris, and then in the early sixteenth century it was in Poitiers, in western France, owned by a canon of the Saint Pierre Cathedal. He left the Breviculum to his nephew in 1582; what happened to the manuscript after that is uncertain. It was bought in 1736 by Ulrich Bürgi, the abbot of the Benedictine monastery St Peter’s Abbey in the Black Forest, from the Freiburg lawyer Joseph Anton Weigel. When the monastery was secularized in 1806/1807, Le Myésier’s illuminated manuscript — and many of the other treasures of the monastery library — became part of the collection of the Grand Duke of Baden’s library in Karlsruhe. Today these manuscripts are held in the Baden State Library, the direct successor of the Duke’s library.

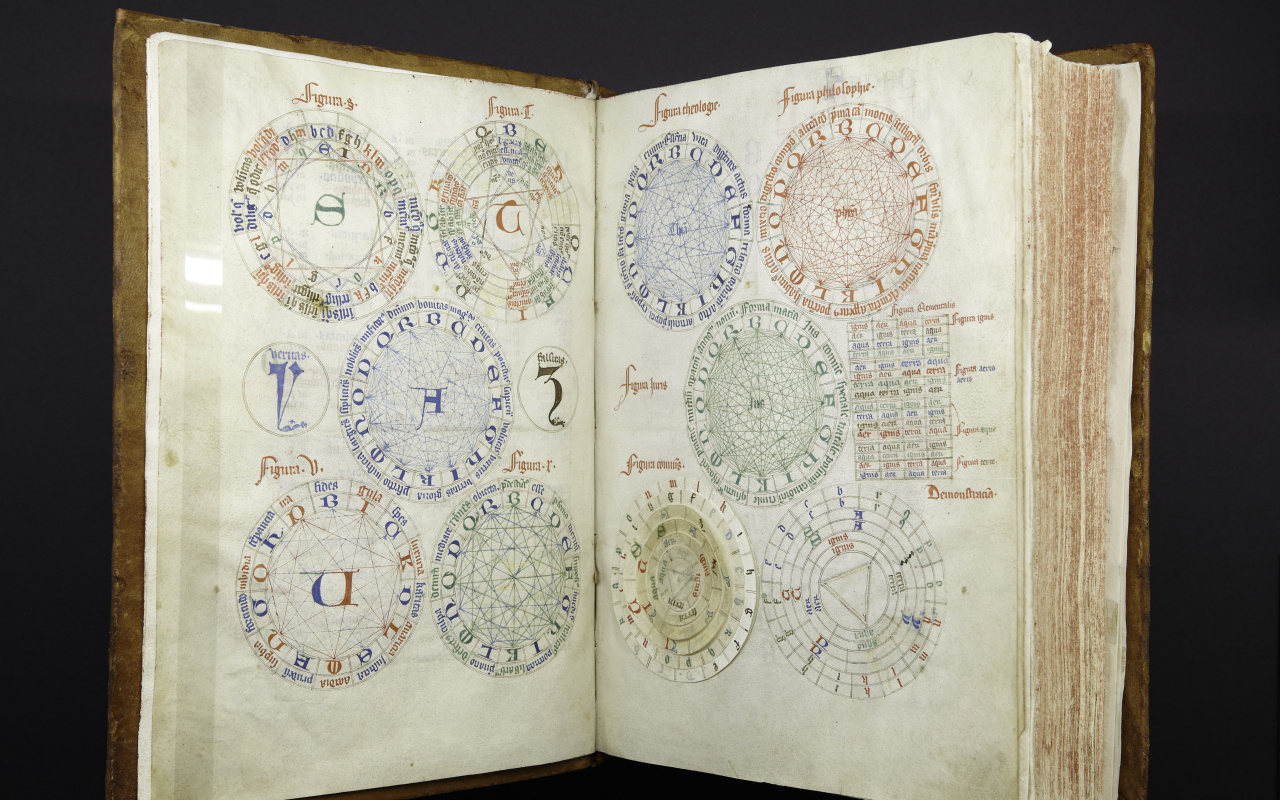

Ramon Llull’s »Ars brevis« (Pisa, 1308) is an abbreviated version of his »Ars generalis ultima«, written in the same year, in which he uses geometrical figures and algebraic notation (letters) to demonstrate the basics of his combinatory methods of absolute and relative principles. Written in Latin, the work enjoyed wide circulation. Well-known are also a Hebrew (1476) and an Arabic version (1682), which gives an impression of the extent of the reception of Llull’s work across the boundaries of the religions. In our times, in which religious irrationalism is again on the increase, it is a gesture both significant and symbolic to exhibit these manuscripts together that are written in the three languages of the Abrahamic religions. They remind us of Llull’s utopia to acknowledge the others in dialogue. He was convinced that understanding between Jews, Christians, and Muslims could not be based on the holy books of the three religions (Torah, Christian Bible, and Koran), but instead on a universal grammar of the names of God, which as the common foundation of the three religions form the rational principles of an »ars combinatoria«.

The philosopher and cardinal Nicholas of Cusa (1401–1464) transcribed in his youth important excerpts from Llull’s works, and had at his disposal a collection of ten codices comprising seventy of his works. This meant that there were more works by Llull than any other philosopher in Nicholas’ extensive private library at the Kueser Hospice, a collection containing numerous works of philosophy, theology, jurisprudence, history, mathematics, astronomy, astrology, and alchemy. Nicholas of Cusa probably came into contact with Llull’s ideas in his youth, during his canonical studies at the University of Padua. In the six years he spent in the city, he discovered Byzantine culture for himself, the new mathematics, and the sources of Venetian humanism. The intellectual environment that Nicholas encountered there was in contrast to his scholasticismimbued studies in Heidelberg, and marked with a dynamic understanding of reality, according to the model of Llull. In the opinion of Charles Lohr, the former director of the Raimundus Lullus Institute of the University of Freiburg: »The linkage of the Venetian vision of human dignity with Llull’s metaphysics triggered a revolution in the history of philosophy.«

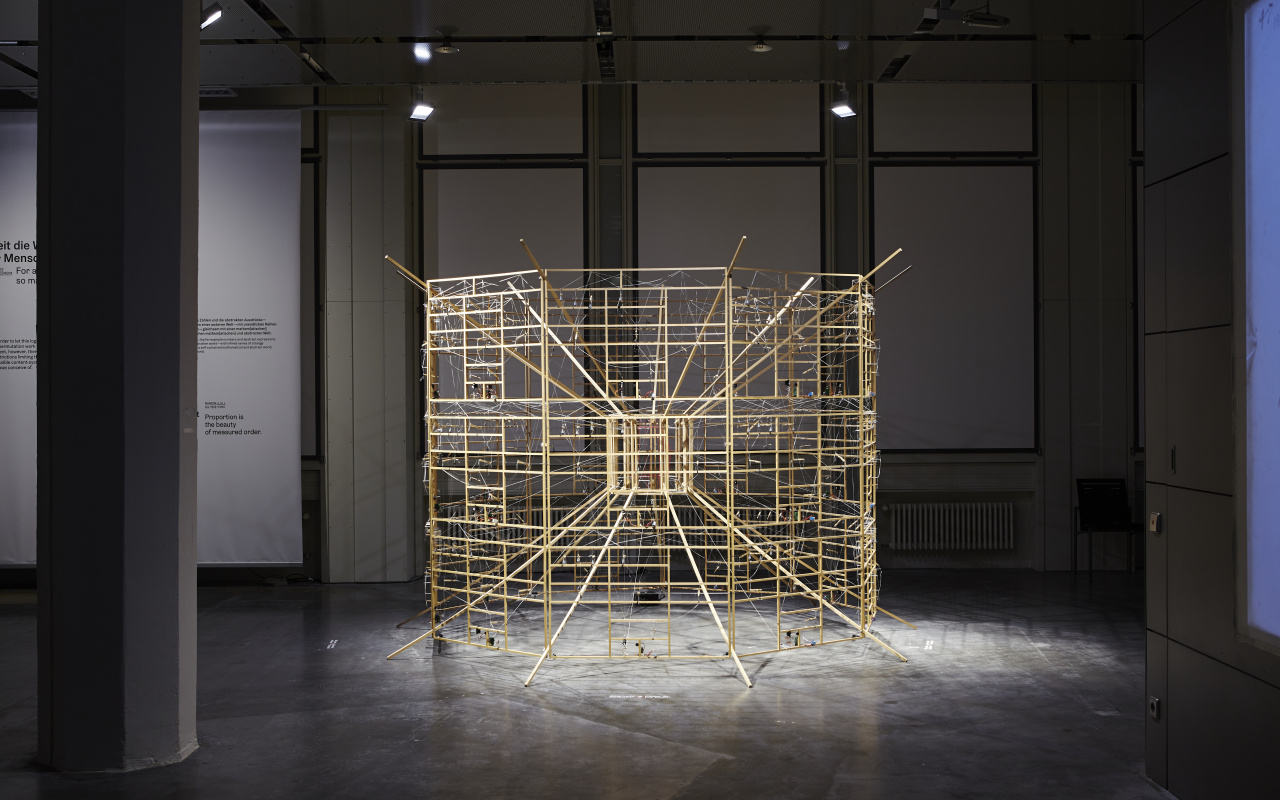

This sculpture leads us into a structure, which could be a calculating machine, into a labyrinthine space with many branches, the components of which, however, are arranged both symmetrically and balanced according to definite principles of order. The construction, which consists of wooden slats, chains, and lead weights, is conceived as a »reverse« machine, which is turned inside out. In its functional way, it copies the logic of neural networks. Through their geometric structure, which can be looked into from all sides, it appears as though they have crossed the line that separates the inside from the outside. However, the inner logic according to which the machine operates remains hidden and the illusion of openness and penetrability is frustrated yet again.

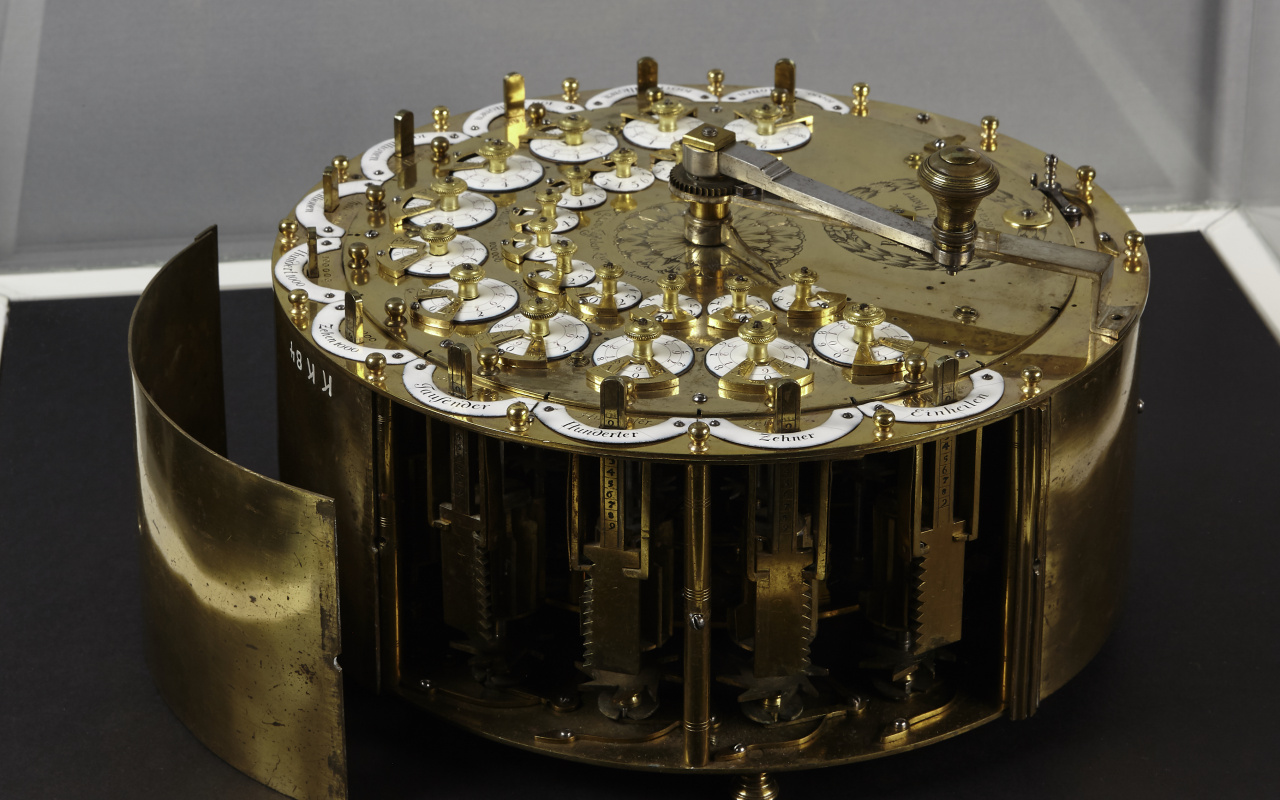

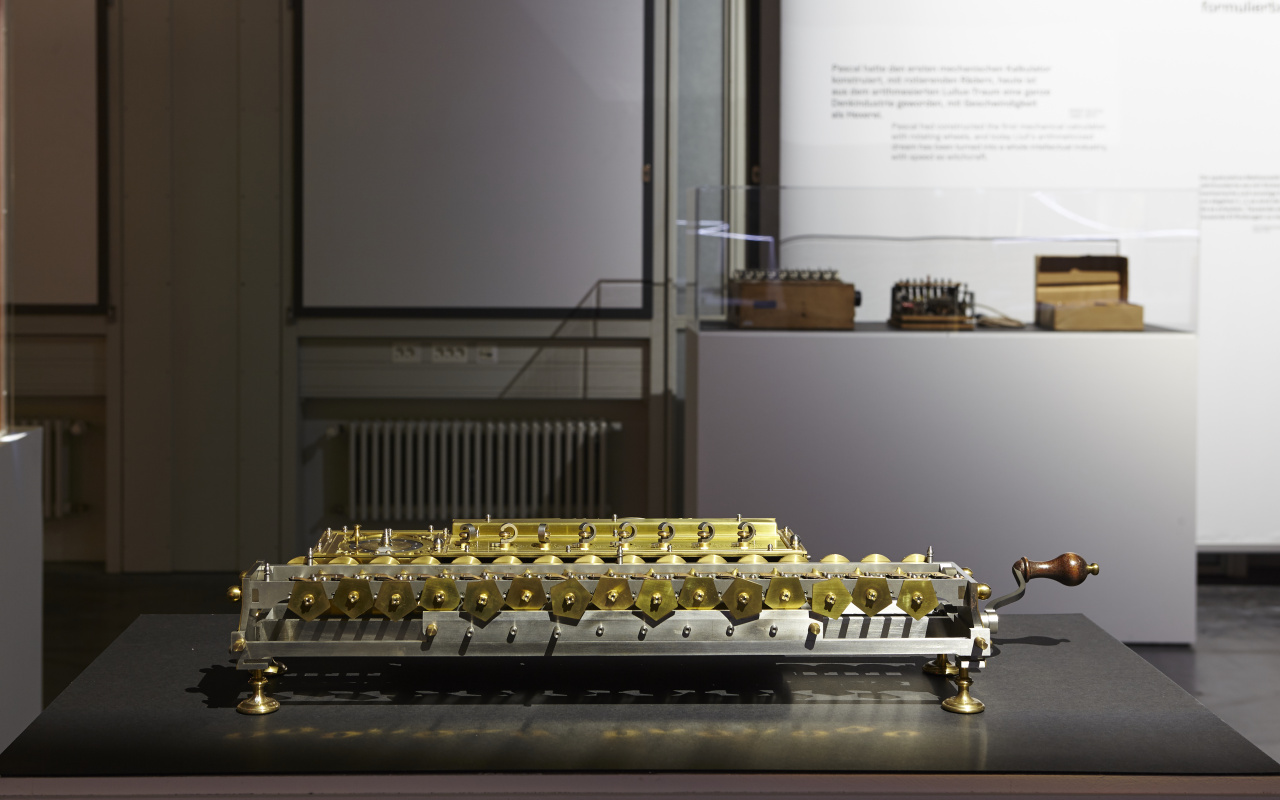

The Philipp Matthäus Hahn (1739–1790) of Württemberg originally came from Kornwestheim near Ludwigsburg. He was a pastor, who in his leisure time devoted a great deal of effort to precision engineering. After studying the calculating machines by Jakob Leupold (1674–1727), who in 1727 had published the first history of the calculating machines in Leipzig, in the 1770s Hahn constructed intricate devices made of brass, which had two sets of twelve circular enamelled dials that operated with a central manual contactor. Together with Antonius Braun (1686–1728), who was also from Württemberg and who built similar machines, Hahn founded the precision engineering industry today’s equivalent of which is the state’s flourishing IT and software industry. Hahn’s aesthetically pleasing and sophisticated artefacts were not actually intended to be used by merchants or early statisticians. As God’s machines of a special kind, their aspiration was to provide proof of the notion that the world functions like an enormous mechanical

In 1666, the German philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) wrote the treatise »Dissertatio de arte combinatoria«, which engages systematically with Llull’s Ars. In the context of his idea of a universal science for everything learnable, and a »lingua universalis«, from 1672 Leibniz worked on developing a calculating machine, which for the first time was able to perform automatically the four fundamental arithmetical operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division). Leibniz’ calculating machine is considered a milestone in the history of mechanical calculating machines. The operating mechanism that Leibniz developed, which is also known as the stepped drum or Leibniz Wheel, it was possible to perform multiplication mechanically. For over two hundred years, this remained an indispensable component of mechanical calculating machines. The exhibit shown here is a fully functioning replica of the only original machine that has survived, which is now in the State Library of Lower Saxony in Hanover. The replica was built according to plans by Joachim Lehmann.

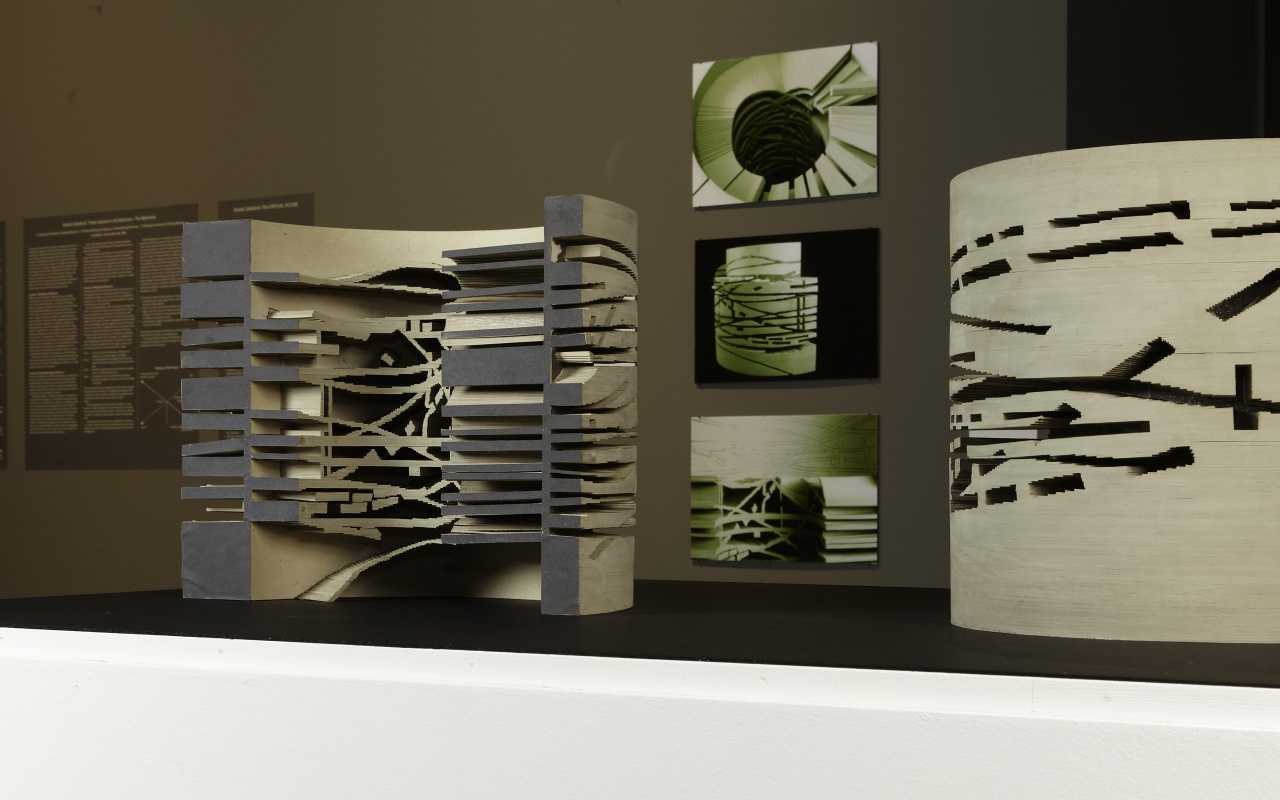

With his design for a »Virtual House« of 1997, the architect and artist Daniel Libeskind did not have some technologically upgraded refuge of the future in mind, which would react to the hype about the »new media« cyberspace and virtual reality at the time. The term virtuality was understood by Libeskind in a much broader way; namely, as a sphere of what is possible. Consequently, his design does not analyze any kind of static form, but a dynamic configuration, which is concerned with the experience at a certain moment.

And although the physical model of the house has to hold fast to a certain moment in time in its material form, Libeskind makes it plain that »The model represents what one can see at a certain moment, but there is no certain moment. […] There cannot be a singular virtual house. The single case is only a token in the actual of the virtual.«

Familiar with the writings of Ramon Llull and Giordano Bruno (1548–1600), who as an astronomer and philosopher assumed the universe was infinite and eternal, Libeskind made a combinatory open principle the structural foundation of the Virtual House. Its cylindrical mechanism would consist of 365 kinetic rings, referring to the 365 days of the year — every day as a possibility for new decisions — which permanently rotate on their own axis in both directions. In total, the combinatory possibilities of the rings represent every possible form, every possible configuration of the house, without ever materializing them.

Philipp Goldbach’s Read Only Memory (ROM) thematizes some of the requirements of digital storage technology: practical, material, theoretical, and historical. The electric conductivity of metals, the process of binary encoding through positive and negative charge states, and the theory of artificial ideal languages, are brought together in his series of entirely handmade circuit boards. On each one Goldbach etched a grid of conductive tracks on double sided copper-plated boards, drilled through them at the intersection points, and connected them to 8000–9000 diodes soldered on both sides.

In this way, bit by bit, in switching states of 0 and 1, Goldbach encoded passages from historical texts that develop ideas and approaches for a lingua universalis. The intense debates in the seventeenth century about a universal or international auxiliary language that would put an end to the Babylonian plethora of languages, reconcile peoples, and convert non-believers were formulated in mathematical and logical terms and can be seen as the conceptual predecessors of digital machine languages. Llull’s »Ars generalis ultima« is the earliest text that Goldbach has included in his series of boards. This work was especially productive for thinkers in the Baroque era and also for today’s computer technology, because Llull’s »logical machine« provided for the first time »hardware« and »software«.

In the tradition of the »OuLiPo – workshop of potential literature« this interactive installation gives visitors the opportunity to recombine the poetic ensemble of the preeminent Singaporean poet Edwin Thumboo. Twenty-seven of his best-known poems are redefined as polyvocal readings that de- and reconstruct his original oeuvre, creating a live performance with continuously emergent vectors of meaning.

The 200 cm-diameter, round wall-projected image shows a clock-like circle of twenty-seven figures of the poet. The visitor uses a circular knob to rotate a white dot around the edge of the circle to choose one of the figures and thereby trigger his reading of a particular poem that will continue until another figure is chosen. By moving the marker from one figure to another the viewer interrupts the ongoing reading and jump-cuts to a different poem and reading. The resulting indeterminate machination of Thumboo’s poetry readings, shown also as printed texts across the center of the screen, constructs an infinitely recombinatory new poetic entity out of his oeuvre.

In a fascinating kind of way Yunchul Kim combines material, electronic, and mathematical algorithmic aspects of our reality. He demonstrates contemporary alchemistic practice at the highest level. In recent years, Kim has built a series of complex artifacts in the pataphysical tradition, which combine heterogenous materials such as liquids, paints, chemicals, and various metals in poetic dynamism. The title of the installation,

Flare, refers to the Flare solution that can be seen moving in the glass reactor. In addition, the work refers to the both nontransparent and influential lobbying that Flare Solutions Ltd. performs for the global oil and gas industry. The Korean artist is currently working at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna as an arts researcher on the project.

In a fascinating kind of way Yunchul Kim combines material, electronic, and mathematical algorithmic aspects of our reality. He demonstrates contemporary alchemistic practice at the highest level. In recent years, Kim has built a series of complex artifacts in the pataphysical tradition, which combine heterogenous materials such as liquids, paints, chemicals, and various metals in poetic dynamism. The title of the installation, »Flare«, refers to the Flare solution that can be seen moving in the glass reactor. In addition, the work refers to the both nontransparent and influential lobbying that Flare Solutions Ltd. performs for the global oil and gas industry. The Korean artist is currently working at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna as an arts researcher on the project »Liquid Things«.

In his autobiography »Vita coaetanea« (Paris, 1311), Ramon Llull describes how he spent a week in deep contemplation on the Randa mountain in Majorca. His eyes were directed heavenward when he had a cosmic vision in which he learned exactly how he should write the book of books to convert people of other faiths to Christianity. The light rooms by the artist Otto Piene (1928–2014), in whose work art, science, and technology fuse, reveal a similar experience of cosmic connection, inspiration, and contemplation. Here, it is possible to experience the dynamic quality of light as it completely embraces the viewer and floats through the room. For Piene, the most important aspect of these rooms is their silence; it is a silence, which sensitizes and opens the mind to an elemental and universal experience of light. Similar to Llull, behind this is the idea of peaceful, humane coexistence, which Piene sets against the horrific experiences of World War II. Fascinated by the idea of painting light, he dreamed of light devices that would fill rooms with light visions. In this way the combination of light, modern technology, and science become the vehicle of a utopia for a society on the threshold of a completely new beginning after the trauma of war.

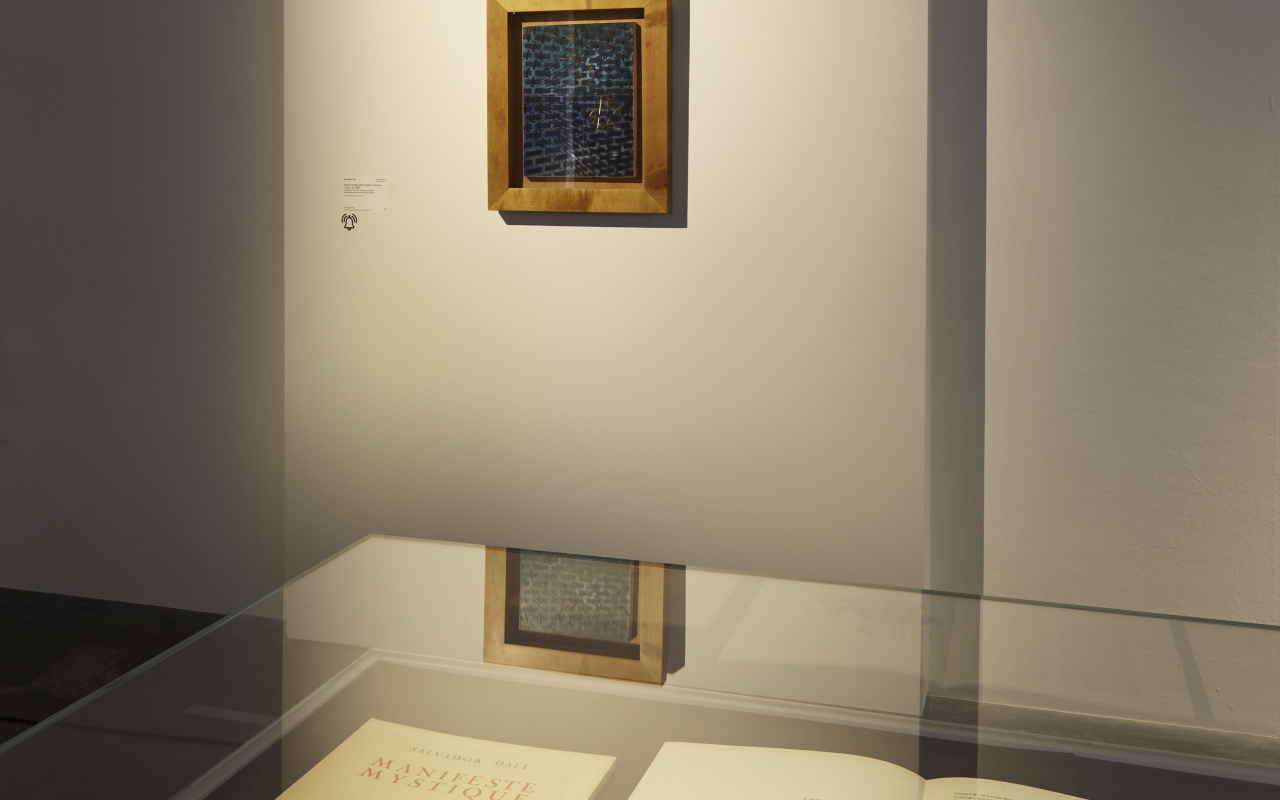

Around 1948, after returning to Europe after his stay in the USA, Salvador Dalí had already formulated his project for the renewal of religious art, which was partly inspired by Renaissance artists (Raphael and Leonardo), and which served as the basis for his »Manifeste mystique« (1951). With this work, which consists of drawings and a text (in French and Latin), Dalí dissociated himself from the ideals of the French Surrealism movement, especially from André Breton (1896–1966). Dalí’s idea was to create a new art, whose mystic-ecstatic foundation were inspired by Ramon Llull, Raymond of Sabunde (c. 1385–1436), the Spanish mystics — such as Juan de la Cruz (1542–1591), to whom he dedicated various paintings –, Juan de Herrera (1533–1597), an architect of El Escorial (monastery and royal palace of Philipp II.), Antoni Gaudí (1852–1926), and the Catalan philosopher Francesc Pujols (1882–1962).

The Catalan artist and poet Perejaume (* 1957) developed a highly unique sensitivity and vision of nature in his important artistic oeuvre. To the concept of place, which is fundamentally connected with the Catalan landscape, Perejaume attaches an enormous amount of importance in his essays. His dialogue with the Catalan tradition includes, amongst other things, poems by Jacint Verdaguer (1845–1902), who wrote poetic versions of Llull’s »Llibre d’amic e amat« [The Book of the Lover and the Beloved], and the paintings by Antoni Tàpies (1923–2012) and Joan Miró (1893–1983). For his approach to the figure of Ramon Llull, Perejaume suggests an audiovisual installation: a Mediterranean forest with rotating trees, traditional Catalan songs, which are based on texts from Llull’s work on medicine, as well as other literary works by the Majorcan philosopher. The totality of the installation conveys the dynamics of the nature and mechanism of the idea that inspires Llull’s »Ars«.

Portolan charts began to be produced in around the same period that Ramon Llull was gradually developing his variant of the »ars combinatoria«. Tuscan cartographers began to make these charts in the last third of the thirteenth century, and as modern cultural techniques of navigation they circulated fast in the major ports of Genoa and Venice, cities which themselves were the results of networking. From there the charts quickly reached Majorca and Catalonia. Portolan charts did not serve either ecclesiastical or other power-political interests. Originating from »portolanos« — pilots’ handbooks — they were exceptionally useful for seafarers. The most obvious aesthetic and technical feature of the charts is their network of lines emanating from windroses, which gave mariners information about directions and distances that were important for steering ships. This very precise example of a Portolan chart of the Mediterranean is a later production. It was made in 1550 by Bartolomeo Olivo on parchment, and is held in the rare books and manuscripts section of the Baden State Library in Karlsruhe.