»Isn’t it time we stopped expecting critics...

...to understand the complexities of art to avoid misunderstandings?«

VON ZKM REDAKTION

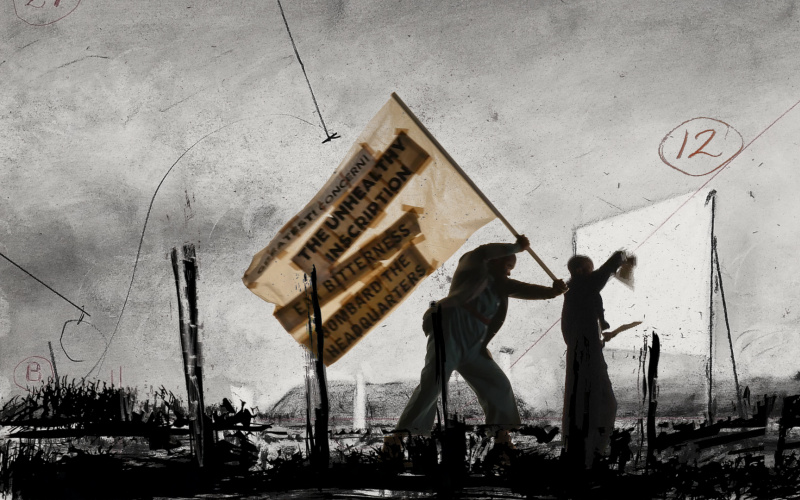

Zum Auftakt der GLOBALE werden auf 7.000 qm2-Ausstellungsfläche, über zwei Lichthöfe, Großinstallationen von Ryoji Ikeda präsentiert: Eine der Installationen, »supersymmetry«, ist im Augenblick in London, Brewer Street Car Park, ausgestellt und sorgte in Großbritannien für Kontroversen: Sollte Kunst naturwissenschaftliche Phänomene kommentieren?

»Why does Cern want artists to respond to it anyway? On this evidence they have little to say about advanced science. Ikeda’s noisy, nervous, annoying artwork merely communicates what any layperson might feel if exposed to hardcore physics. This array of beeps, whooshes, dazzling strobes and light pulses basically seems to be rubbing its head and groaning: 'Blow me, this is complicated stuff.'«

– »Should art respond to science? On this evidence, the answer is simple: no way« article by Jonathan Jones in: The Guardian, April, 23, 2015

Response by Peter Weibel to the article by Jonathan Jones in: The Guardian, April, 23, 2015

»If an impressionist painter creates a picture of a flower, no critic expects the painting to be a contribution to the science of biology. At its best, it is the result of an artist's application of color theory after having studied more or less intuitively scientific color theories. A landscape painting is not expected to make a contribution to the science of geology, etc.

But even in painting science was a beneficiary for the arts. In his famous Treatise on Painting – written around 1495, first published in Italy, France in 1651 and in Germany in 1724 – Leonardo da Vinci proclaimed »painting is a science«. In the siècle d’Or – in the seventeenth century – painting was part of a network of sciences. Landscape painters such as Pieter Jan Snyers were in close collaboration with geometers, cartographers, and engineers aiming at discovering new modes of depictions of landscapes. Eagerly they reached out and beyond their perceptions of landscapes and scenic views that were common to natural eyesight.

For a fairly long time, painters actively contributed to a glorious engineering culture. However, times have changed. According to the contemporary German painter, Gerhard Richter, we only live »in the ruins of a great painting culture« today.

It holds as one of the paradoxes of modernity that modern painting by way of its furious program of reduction (e.g. monochromatic paintings) and due to its paradigm of self-expression forfeited this solid classical link between science and art.

Scientific legitimation of how to organize sound

Much in contrast to modern painting, both architecture and music of the twentieth century were not governed by such an appeal of deregulation. Especially musicians, such as Arnold Schoenberg with his dodecaphony, Pierre Boulez with his approach to serial composition, or Karlheinz Stockhausen with his algorithmic composition techniques were eagerly searching for a scientific legitimation of how to organize sound. This is the tradition in which Ryoji Ikeda operates today.

Ikeda is extending his tonal material from music to noise and beyond classical musical composition techniques, as a consequence to the innovations having taken place in twentieth century music, and technology. New sounds were provided by artists at the beginning of the twentieth century: The Art of Noises (L'Arte dei Rumori, manifesto by Luigi Russolo, 1913).

Ikeda is only inspired by science

Ikeda's composition techniques are inspired by logical sources, such as algorithms and principles of quantum mechanics. His parameters of composition are built on scientific principles and not on individual expression. His music is not a commentary about science and quantum physics – this is a deep misunderstanding. Mr. Jones is right, with his notion, that Ikeda has little to say about advanced sciences. But Mr. Jones is wrong, when he expects Ikeda to have the intention to say something about science.

No, Ikeda is only inspired by science, because in creating his work, he is confronted with the troubles of classical symmetry and harmony – an artistic struggle, which he shares with science and contemporary architecture (e.g. Greg Lynn). In fact, that harmony and symmetry have been universal principles of the arts for centuries – from architecture to music – can be traced back by insightful studies, such as Hermann Weyl (Symmetry, 1952) or István Hargittai (Symmetry. A Unifying Concept, 1994), and from Gibbs-symmetry (J. W. Gibbs, Elementary Principles in Statistical Mechanics, 1902) to Wigner-symmetry (1959), and the mathematical concept of Lie groups (i.e. representations of continuous symmetry).

Artists and scientists have been allies in search for symmetry

But in 1957 Chen-Ning Franklin Yang and Tsung-dao Lee received the Nobel prize for proving experimentally the violation of the parity principle (compare: Yang, C. N., Symmetry Principles in Physics, 1965). Since then, scientists have been looking for new concepts of symmetry, like super-symmetry in quantum mechanics. Why should a contemporary artist suddenly not be allowed to take part in an advanced search for a new symmetry? For centuries artists and scientists have been allies in their search for symmetry.

In his artistic research Ikeda is not concerned with trying to understand what is going on at CERN like a scientist would. For him, CERN was a source of inspiration in his quest to understand better the contemporary big data environment and the infosphere. What Ikeda shares with CERN are concerns about symmetry and the observable data within our event horizon. Yes, Mr. Jones, Ikeda is concerned with the wonders of nature and expresses it by way of using data. And he does so, because the equation of the twenty-first century appears to be a relation between media, data and men.

This formula expresses the up to date version of the equation of the twentieth century as formulated by F. L. Wright (Machinery Material, and Men). In this respect Ikeda is a prototypical artist of the beginning of the twenty-first century. Consequently, the ZKM in Karlsruhe gives him a prominent position in presenting Ikeda's latest production right at the opening of ZKM's new art manifestation »GLOBALE. The new art event in the digital age«, starting 19, June, 2015.«

![superysymmetry [experience], audiovisuelle Installation, 2014 / © Ryoji Ikeda, Foto: Ryuichi Maruo Ein Mensch läuft zwischen zwei Reihen von Bildschirmen her](/system/files/styles/img_para_media_detail/private/field_media_image/2023/02/23/101414/susy_experience_1.jpg?itok=8_jH2a2U)