Introduction to the exhibtion

Global Games – The Significance of Computer Games

With the exhibition »Global Games« the ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe highlights the increasing relevance of computer games by presenting the latest developments in this field. The computer game is a child of the digital revolution and thus a medium produced by the infosphere. Moreover, the apparent paradox of serious play – in so-called »serious games« – evidences not only the scientification of our culture and the trend toward new tools driving the exo-evolution; but also a new alliance between art and science – a Renaissance 2.0. Computer games represent a popular form well suited for the illustration of socially relevant processes of globalization, radical changes in the media, and digitalization. Computer games serve science and bear didactic potential. Computer games are powerful new tools.

Computer games transport real-world references, meanings, and ideologies, and can hence function as political and social media – in a positive, enlightening way or in the sense of seductive propaganda.

Games thematize such topics as the Syrian conflict, the deployment of drones in war zones (»Unmanned«), the globalized economic interconnectedness of international finance (»Cart Life«), surveillance (»Vigilance 1.0«, »TouchTone«), the situation of refugees at the European borders (»Frontiers«, »From Darkness«), deplorable social states of affairs caused by turbo-capitalism (»Outcasted«), as well as gender issues (»Perfect Woman«, »Dys4ia«), to name but a few. They pose moral questions (»Papers«, »Please.«) and deliver history lessons (»The Cat in the Group«).

They can also be used as teaching aids (»Kerbal Space Program« and »Ludwig«, for example) for use in high school physics courses. By informing about waste separation, the game »Die Müll AG« [Garbage Inc.] aims to raise children's awareness of the topic.

As new tools, games stand for a new craftspeople and their so-called maker culture. Computer games propose utopias and provoke thought – also in the science fiction sense – about (possible) new implements (»Portal«). Or players steer living single-celled euglena with optical impulses in a football match (»Euglena Soccer«). The game »Phone Story« shows the dark side of the iPhone, which is the very reason why Apple has censored it in its app store. In the exhibition »Global Games«, »Phone Story« can be played as intended: on an iPhone.

They can also be used as teaching aids (»Kerbal Space Program« and »Ludwig«, for example) for use in high school physics courses. By informing about waste separation, the game »Die Müll AG« [Garbage Inc.] aims to raise children's awareness of the topic.

As new tools, games stand for a new craftspeople and their so-called maker culture. Computer games propose utopias and provoke thought – also in the science fiction sense – about (possible) new implements (»Portal«). Or players steer living single-celled euglena with optical impulses in a football match (»Euglena Soccer«). The game »Phone Story« shows the dark side of the iPhone, which is the very reason why Apple has censored it in its app store. In the exhibition »Global Games«, »Phone Story« can be played as intended: on an iPhone.

One thing is evident: Computer games are political media that apply their own specific means to topics of social and global political relevance. They do so, on the one hand, in an enlightened manner, within the context of the Games for Change movement. Conversely, the procedural rhetoric is also used as propaganda, as demonstrated in the game »America's Army«, commissioned by the US government as a recruiting tool and distributed free of charge.

The connection between computer games and the military context – the military entertainment-industrial complex – goes all the way back to the early days of the medium. Technology that is invented and developed in the military context diffuses, as mass media, into society and then begins to serve entertainment. In 1958, US physicist William Higinbotham constructed the video game »Tennis for Two« – the prototype of all computer games. In 1945, Higinbotham headed the electronics department of the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, New Mexico, USA. In this context, the invention of the computer game has been called an »arms by-product« (see: Konrad Lischka, »Spielplatz Computer: Kultur, Geschichte und Ästhetik des Computerspiels«, 2002, p. 19). In this media-theoretical commentary, Friedrich A. Kittler generalizes, with respect to the military, industry and the media: "The entertainment industry is, in any conceivable sense of the world, an abuse of army equipment." (Friedrich A. Kittler, »Grammophone, Film, Typewriter«, 1999 [1986], pp. 96–97).

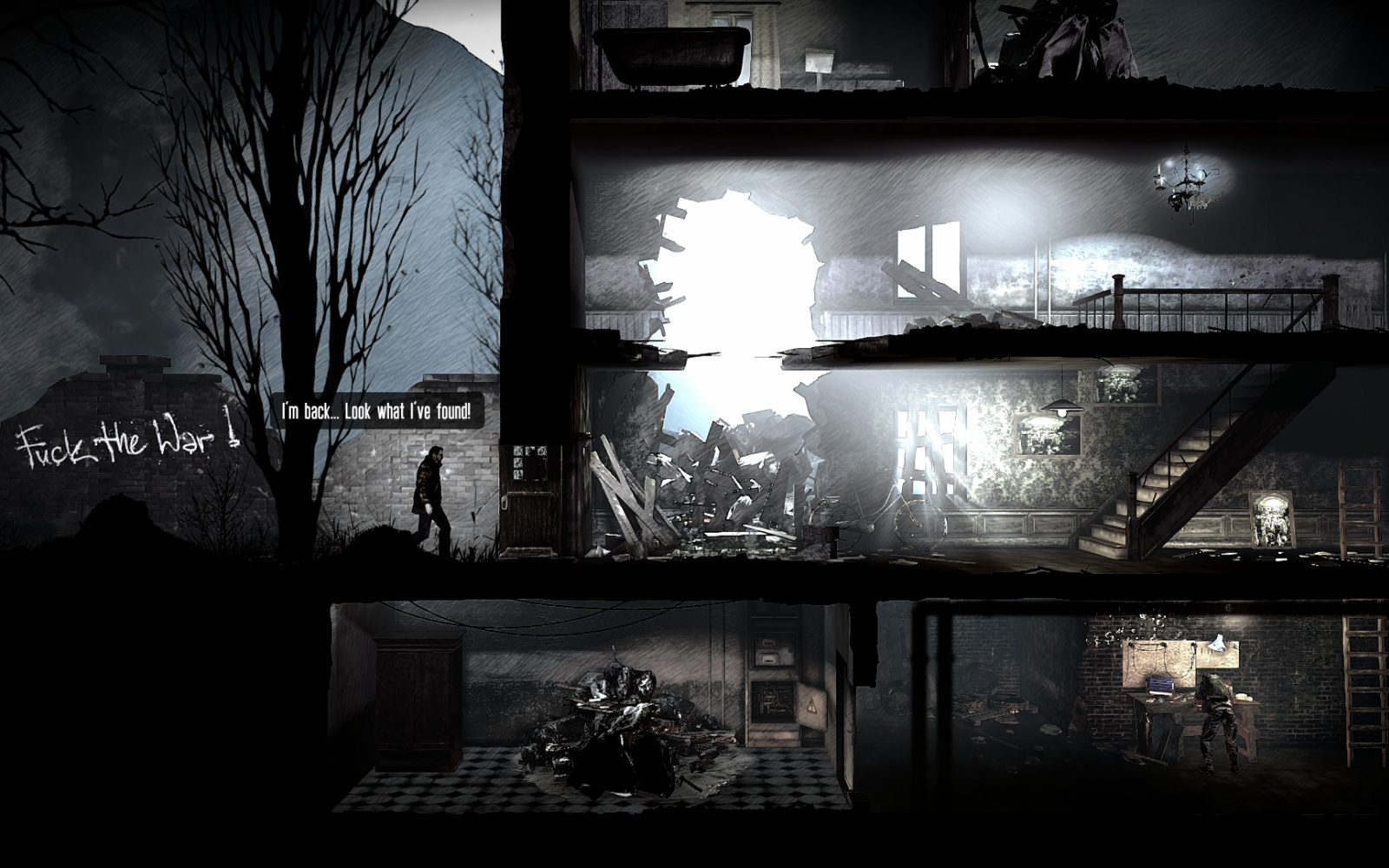

In the independent scene, there are signs of an emerging awareness for antiwar games, as demonstrated, for example, by the German game »Spec Ops: The Line«. In the exhibition »Global Games«, we present »This War of Mine«, from Polish developer 11 bit studios, which conveys an experience of war from the perspective of civilians.

Computer games provide commentary on current world events. The game »September 12th: A Toy World«, by Gonzalo Frasca from Uruguay, uses simple caricaturistic means to present the spiral of violence propelled and entrenched by the US War on Terror. The game »Yellow Umbrella« ties directly into recent protests in Hong Kong. Another example of caricature in the exhibition »Global Games« is »Faith Fighter« by Paolo Pedercini. While referencing such genre classics as »Street Fighter II«, this beat 'em up does an ironic take on their stereotypical – and even racist – portrayal of fighters from around the world, as it pits representatives of the major world religions against each other. Jesus faces off against, among others, Buddha and Mohammed.

The connection between computer games and the military context – the military entertainment-industrial complex – goes all the way back to the early days of the medium. Technology that is invented and developed in the military context diffuses, as mass media, into society and then begins to serve entertainment. In 1958, US physicist William Higinbotham constructed the video game »Tennis for Two« – the prototype of all computer games. In 1945, Higinbotham headed the electronics department of the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, New Mexico, USA. In this context, the invention of the computer game has been called an »arms by-product« (see: Konrad Lischka, »Spielplatz Computer: Kultur, Geschichte und Ästhetik des Computerspiels«, 2002, p. 19). In this media-theoretical commentary, Friedrich A. Kittler generalizes, with respect to the military, industry and the media: "The entertainment industry is, in any conceivable sense of the world, an abuse of army equipment." (Friedrich A. Kittler, »Grammophone, Film, Typewriter«, 1999 [1986], pp. 96–97).

In the independent scene, there are signs of an emerging awareness for antiwar games, as demonstrated, for example, by the German game »Spec Ops: The Line«. In the exhibition »Global Games«, we present »This War of Mine«, from Polish developer 11 bit studios, which conveys an experience of war from the perspective of civilians.

Computer games provide commentary on current world events. The game »September 12th: A Toy World«, by Gonzalo Frasca from Uruguay, uses simple caricaturistic means to present the spiral of violence propelled and entrenched by the US War on Terror. The game »Yellow Umbrella« ties directly into recent protests in Hong Kong. Another example of caricature in the exhibition »Global Games« is »Faith Fighter« by Paolo Pedercini. While referencing such genre classics as »Street Fighter II«, this beat 'em up does an ironic take on their stereotypical – and even racist – portrayal of fighters from around the world, as it pits representatives of the major world religions against each other. Jesus faces off against, among others, Buddha and Mohammed.

Computer games are in no way a purely Western phenomenon, but must be considered a global medium. Games are produced and played all over the world. Little known are computer game productions from the Arab world and the Near East. Two noteworthy examples are from Syria and Iran. Published by Syrian game developer Dar al-Fikr and played from a Palestinian perspective, the shooter »Under Ash« (2001) and its follow-up »Under Siege« (2005) stage the battle against Israel during the second Intifada from 1999 to 2002. And the Iran Computer & Video Games Foundation promotes Iranian games, presenting them at such computer game trade fairs as the Gamescom in Cologne. At »Global Games«, visitors can also experience the sole computer games from the former GDR: The home console »Bildschirmspiel 01« [Video Game 01]; as well as the gaming machine »Poly-Play«, with such games as »Hirschjagd« [Deer Hunt] and »Hase und Wolf« [Hare and Wolf].

Serious games, such as the puzzle games »Foldit«, »EyeWire«, »EteRNA« or »Nanocrafter« are based on scientific data and include such data in their gameplay. Gamers are transformed into interconnected citizen scientists. Playful interaction with the games generates data that, in turn, flows back into the scientific research, often resulting in important findings. In this fashion, the puzzle game »Foldit« provided substantial insight into the structures of a protein causing AIDS in apes. This sort of work is referred to as citizen science, meaning the delegation of certain scientifc research tasks to (scientific) amateurs. Citizen scientists help making observations, evaluating data, and performing measurments. Disguised as a computer game, this camouflaged work is certainly performed much more readily – the phenomenon, in turn, is known as gamification.

»Global Games« illustrates the range of computer games as a politically and socially relevant medium. »Global Games« is interactive in its presentation, i.e. all the exhibits are playable. Specially produced »Let's Play« videos explain the games and convey an impression of the gaming experience – even if one choose not to actually play.

Author: Stephan Schwingeler

Serious games, such as the puzzle games »Foldit«, »EyeWire«, »EteRNA« or »Nanocrafter« are based on scientific data and include such data in their gameplay. Gamers are transformed into interconnected citizen scientists. Playful interaction with the games generates data that, in turn, flows back into the scientific research, often resulting in important findings. In this fashion, the puzzle game »Foldit« provided substantial insight into the structures of a protein causing AIDS in apes. This sort of work is referred to as citizen science, meaning the delegation of certain scientifc research tasks to (scientific) amateurs. Citizen scientists help making observations, evaluating data, and performing measurments. Disguised as a computer game, this camouflaged work is certainly performed much more readily – the phenomenon, in turn, is known as gamification.

»Global Games« illustrates the range of computer games as a politically and socially relevant medium. »Global Games« is interactive in its presentation, i.e. all the exhibits are playable. Specially produced »Let's Play« videos explain the games and convey an impression of the gaming experience – even if one choose not to actually play.

Author: Stephan Schwingeler