New Cartographies of Art

The year 1989 bore witness to a worldwide upheaval which, in turn, spawned a new age for art (Alexander Alberro). »Globalization« superseded art's old »international,« over which a western flag flew, providing many artists with the opportunity to participate for the first time.

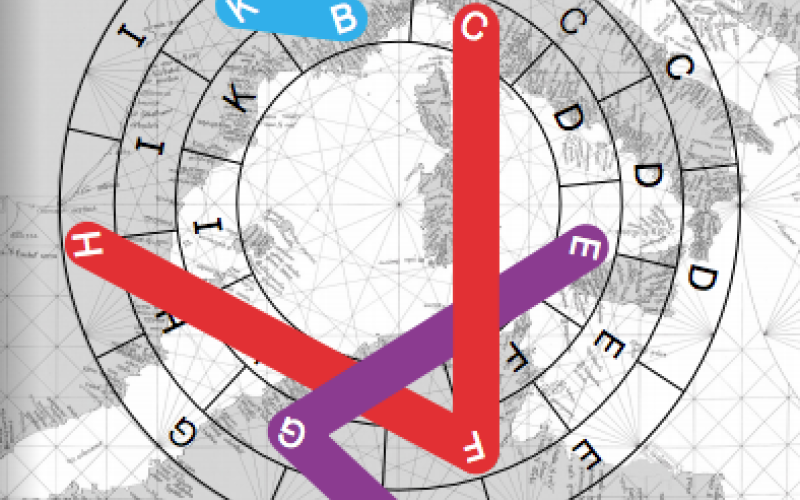

The attempt to draw up a new world map accounting for these changing circumstances also poses the question of de-signation. Talk of center and periphery has become redundant. Regions that were hitherto not at the center now jostle for new ascriptions. Therefore, the term »third world« sounds not only antiquated today, but also defamatory; the alternative »global South« is nothing short of flat and vapid. In their search for new terminology during the 1990s, Australians ushered in the term »Pacific-Asian Art« as a region of art in their endeavor to reposition themselves against the backdrop of problems connected with national culture. Do national boundaries have any relevance? Is art from the Maghreb African, or does it instead fall within the Mediterranean region? Is Iran part of the Middle East or a region in its own right? On the other hand, it is indisputable that the Eurocentric monolith is crumbling, and that by way of a »provincialization« processes in Europe (Dipesh Chakrabarty), relations and contexts within the world of art can now be rethought.

In the course of globalization, the theme of migration becomes less important. Contemporary technologies, such as video and installation, facilitate the global spread of media art. The potential public grows and the question is no longer one of where artists actually live, but where and how they find their audience.

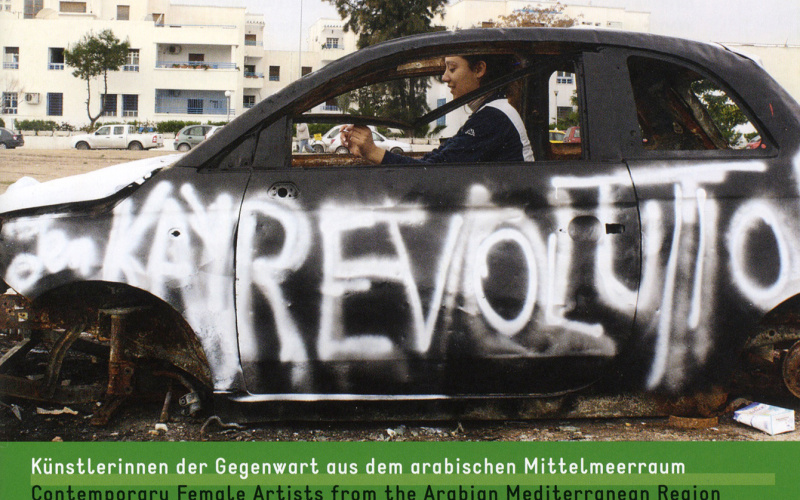

The global process in art occurred at the same time as the World Wide Web’s march to victory. Since 1994, the Web has existed as a technology promising free access; yet it is not universal in terms of either content or usage; instead, it is polycentric and populated by private users. Hence, it is capable of generating agitation in the public realm and presents a threat to political regimes, which consequently want to censor it. Similar problems apply to the activities of artists who work beyond the protection of a recognized art scene. They trigger political conflicts wherever art does not enjoy professional freedom, or is unable to attest to its own tradition. In such places, through their actions, artists appear to undermine local mass media monopolies. The World Wide Web has accelerated the distribution of global art in a variety of ways, as it allows communication without the necessity of a travel visa.

The globalization of art is nowhere more evident than in art markets. The New Economy has brought forth a new clientele of billionaires who collect contemporary art as a symbol of a global lifestyle. New centers of art, such as Hong Kong, Singapore, and Dubai, challenge the old ones of New York, London, and Paris. The boom in contemporary art can also be witnessed in the worldwide spread of MOCAs (museums of contemporary art), which have superseded the model of MoMA (museums of modern art).

One further phenomenon connected with the emergence of new art worlds is the proliferation of biennials. Whereas, roughly two dozen of these periodically organized exhibitions were in existence in 1989, the year 2000 saw the establishment of a further forty such events. Today, there are over 200 biennials. The new venues are located, for the most part, in newly industrializing nations, which, after having flourished economically in the course of globalization, now aspire to international networking. Meanwhile, with the spread of the biennial format, a variety of discourses and concepts have emerged, which also grapple with a new cartography of art beyond national borders.

Author: Andrea Buddensieg