2014-01-30

Fashion Victims

Art Activism and the Mask of the Institution

“[…] we may see the overall meaning of art change profoundly

– from being an end to being a means, from holding out a promise of perfection

in some other realm to demonstrating a way of living meaningfully in this one.”[1]

It’s very fashionable to be doing politics in the institutions of contemporary culture at the start of the twenty-first century. But despite the number of biennials, festivals, and museum exhibitions plastering the words activism, social change, resistance, and political all over their publicity, the majority of the works are simply representations of activism, pictures of politics, fictional insurrections, micro gestures with little strategy for how they might evolve into any meaningful social transformation. Within the cold white walls and sombre black boxes of these institutions there is rarely any effort to use art and creativity to build effective forms of resistance but a lot of effort enclosing protest tactics into the realm of art, as if it were a zoo for exotic species – the “real activists.” Perhaps in an age of extreme ecological and social crisis, the key questions artists-activists need to ask themselves are: Can these institutions be machines for amplifying our potential to transform the status quo, or are they palaces carefully engineered for us to play the fool in, whilst outside the kings and queens continue to play Russian roulette with our future while enriching theirs?

___

For the last decade Isabelle Fremeaux and I have co-facilitated The Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination (Labofii), a collective which brings artists and activists together to design and enact new tools of resistance, whilst experimenting with forms of postcapitalist life. Sometimes we work embedded in protest movements, such as when we invented the Rebel Clown methodology and toured the UK recruiting a several hundred-strong clown army against the G8 summit.

Sometimes the work is pedagogy, such as running workshops in permaculture design and art activism for young artists and activists. Sometimes we begin in an institutional theatre and then take the audience outside with us to become disobedient actors in the public realm; this has included arming the audience with ants that sabotage computers and letting them loose on the doorsteps of banks who fund fossil fuel extraction, or leaving the stage with a swarm of hundreds of bikes fitted out with a mobile pirate radio station sound system occupying the city streets. Sometimes it’s as simple as organizing a playful snowball fight between the people and bankers in London’s financial district. Sometimes it’s as complex as launching a rebel raft regatta (complete with buried boats and treasure maps) to shut down an EON coal fired power station. Sometimes it’s long term and slow, such as setting up a commune in Brittany which includes an organic farm and school of art activism.

Inspired by Joseph Beuys’ notions of social sculpture, our material is the social movements themselves, movements in which we work as organizers and activists as much as artists. In fact we try to define ourselves outside of either of these labels. The notion of artists assumes a certain monopoly of creativity held by a cultural elite, denying the creativity within everyday life – cooking, farming, child rearing, teaching, etc. – whilst the notion of activist reinforces the existence of a specialist cadre of people who are in charge of social transformation, similarly denying the political dimension of everyday life.

Key to the practice of the Labofii is the refusal to represent politics. Instead of just making videos, installations, or performances about politics, we attempt to use the creativity inherent in artistic practice to develop effective new forms of resistance. Every political form, from the protest march to the strike, the placard to the boycott, the occupy camp to industrial sabotage, was the fruit of a creative thought, enriched by the courage to carry it out directly in the material reality of everyday life.

The philosophy of direct action lies at the root of our work. Direct action is not about denouncing, it’s not about asking politicians to do something for us, it’s not about communication issues in the hope of convincing other people to change, it’s not about raising consciousness, but doing things directly: shaping life here and now, together.

The art of direct action is providing immediate hands-on solutions to a problem. If you understand that people are homeless, you don’t just “explore” the issue, you don’t make a documentary or an exhibition about it, you open a squat to house them or set up a counter-institution that resists unaffordable forms of housing schemes. If you see one of the oldest forests in Europe being destroyed by RWE for an opencast coal mine, such as is happening to the Hambacher Forst [Hambacher forest] near Cologne, you occupy the trees and put your body in the way of the chain saws and bulldozers. It’s an art that requires as much courage as it does creativity.

___

What our generation is living through is the final confrontation between neoliberal capitalism’s need for infinite growth and the finite resources of the planet, and no amount of financial speculation or high tech intervention will buy this system its way out of the inevitable crash.

The Labofii does not believe this culture will somehow undergo a voluntary transformation into a sane, equitable, and sustainable way of living. We think that we have to undo this culture completely and rebuild entirely different ways of being and sharing of our worlds. No real solutions to this crisis will be put in place by those in power if it means them not profiting from it. As escaped slave Frederick Douglas knew so well when he was fighting the horrors of the slave trade and declared “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will. “

The goal of activism for us can be summed up in a sentence: to remove the ability of the rich to steal from the poor, and dismantle the ability of the powerful to destroy our biosphere. The role of art is to make this activism as creative, desirable, and effective as possible – to stop the war of money against life.

100 million people died in the wars of the last century; another 100 million are expected to die due to climate chaos over the next 18 years, nearly all of them people with life styles that produce very little CO2. The climate catastrophe is not only a war on the biosphere, it is war on the poor, and many of the so-called “solutions,” such as “green capitalism” and nuclear power, are simply toxic illusions that continue the war under a different name. It is a war none of us can escape from, its weapons are everywhere, even here in the global aCtIVISm show, but I’ll come to that later.

Whilst the art of representing politics seems to be easily recuperated by culture institutions, the art of direct action, however, seems less palatable, as our experience in the Labofii has taught us.

___

In 2010 we were invited to hold a two-day public workshop in art and activism in London’s contemporary art museum, the Tate Modern. We entitled it: “Disobedience Makes History.” The curators wanted it to end with a public “performance intervention.” They were proud to hold the workshop and put it on the front page of the Tate’s website. A week before the workshop we got an e-mail: “Ultimately, it is also important to be aware that we cannot host any activism directed against Tate and its sponsors,” the curator continued “however, we very much welcome and encourage a debate and reflection on the relationship between art and activism.” One of the Tate sponsors is oil giant BP. We realized this was the best teaching material we have ever been given.

Every day Tate scrubs clean BP’s public image with the detergent of cool progressive culture. But there is nothing innovative or cutting edge about a company that knowingly feeds our addiction to fossil fuels despite a climate crisis, a company whose greed has killed twenty-one employees in just over a year, a company that continues to invest in the cancer-causing climate crimes of tar sands in Alberta, Canada.

By placing the words “BP” and “Art” together, the destructive and obsolete nature of the fossil fuel industry is masked, and crimes against the future are given a slick and stainless sheen.

Every time we step inside the museum Tate makes us complicit with these acts, acts that will one day seem as archaic as the slave trade, as anachronistic as public executions. Every time Nicholas Serota is asked how a museum that prides itself on dealing with climate change can be funded by an oil company, he responds that there are no plans to abandon BP sponsorship. The fact that the chair of the Tate’s board of trustees is the ex-CEO of BP obviously has nothing to do with it!

___

The workshop began on a cold winter’s day, in a slick glass and wooden-paneled room at the top of the museum. We projected the curator’s e-mail onto the wall and asked the workshop participants whether we should obey or disobey the Tate’s orders. The curators tried to sabotage the beautiful heated discussion. It made great drama and even better pedagogy.

After a few hours of debate, the participants decided to disobey; the action would be planned by them at the next workshop. On the eve of the following workshop I was summoned to a meeting with three curators, and the head of security and public services. They told me that if we do anything against BP, they will shut the workshop down. “You are censoring us?” I asked. “That’s a very emotional word to use,” I am told, “and anyway we respect the intellectual content of your work.” The meeting lasted over two hours. I left even more determined to disobey.

At that moment I realized that the Labofii will never be invited back to the Tate. But to make art in the service of life sometimes means letting go of all the promises of fame and fortune that institutions lure us with. As the Zapatista indigenous rebels say “We are already dead, therefore you cannot kill us.” There was nothing the Labofii wanted from the Tate, the freedom to no longer be dependent on the institution was exhilarating, we had well and truly sunk our cultural capital and it felt liberating.

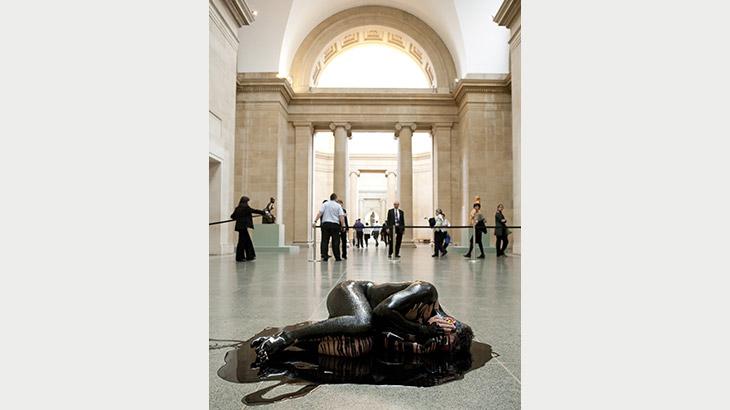

The next day the students created a simple action against BP’s sponsorship of the museum, and afterwards set up a collective called Liberate Tate, which continues today to work to free the Tate from its oil barons. A few months after their founding they made global headlines when they poured hundreds of liters of black molasses inside and outside the Tate, during its party celebrating 20 years of BP sponsorship, held while oil gushed into the Gulf of Mexico.

Since then over a dozen actions have taken place: a body lying naked covered in oil on the floor of the museum, a 16.5m wind turbine blade carried by a hundred people and donated to the Tate as a gift from the nation, an alternative audio guide tour.

The actions have grabbed media attention, from the front page of the Financial Times to articles in the art press, BBC TV news to local radio stations and a public debate around the ethics of corporate sponsorship of culture has been thrown open, all thanks to the Tate’s clumsy attempt at censorship!

The argument is always: “We take money from sponsors who have no power over our programming and we are free to curate what we want.” Of course no order came direct from BP to stop the “Disobedience Makes History” workshop, the censorship was preemptive self censorship, the police man in our heads is always more powerful than any order from on high.

Nowadays before we are invited by an institution we look at the corporate partners and make a strategic decision whether to accept the invitation or not. I have to admit that when I agreed to write this blog and come to Karlsruhe for a discussion at ZKM I completely forgot to look at the corporate partners of the museum. It was only one dark night when I started to write this blog and outside the storms and floods were ravaging Europe that I remembered to look at the corporate partners of ZKM. And there on the front page of the ZKM website – amongst all the good sounding words and phrases such as “Global Activism,” “socio-political significance of civil engagement in the twenty-first century,” and “the future of activist artists as citizens” – was the logo: EnBW.

Why would EnBW need to clean its image with the cool mask of “radical” contemporary culture, I asked myself? Perhaps it is because it continues to run half a dozen coal-fired power stations that are not only directly responsible for the climate holocaust that is taking our world to a place with temperatures similar to hell, but also releases a constant stream of mercury, nitrous oxides, sulfur dioxide, and a range of other toxins that enter our bodies and inflict serious damage on our soft vital organs. Perhaps it is because EnBW’s three nuclear power stations don’t seem as future-safe after the Fukushima disaster, which continues to pump cancer-causing radiation into the land and sea three years on from its meltdown. Perhaps it is because EnBW is under investigation for deals between Morgan Stanley and the ex-French owners Areva who overcharged the Land Baden-Wuerttemberg 780 million euros for shares in the company. Perhaps it is because they paid 280 million euros worth of bribes to Andrej Bykow, who in turn bribed Russian officials and companies to allow the EnBW access to the Russian gas and uranium industry.

It comes as no surprise that another cultural institution is providing the social approval and progressive sheen on a company whose toxic activities have nothing to do with a sustainable and just future, and even less with any form of activism. In fact the best way to look at it is not that these companies are supporting the arts, but that the arts are supporting their lie that they care about anything other than making profits, even though it means annihilating the life support systems of this planet. In fact this kind of sponsorship is an act of anesthesia, something that numbs us, stops us perceiving the reality that is at the root of our poisonous capitalist culture; it is quite the opposite of an aesthetic act, an act that enables us to feel the world, to sense it deep within our guts.

Perhaps the role of the art activist today is not to build our cultural capital by supporting such institutions, not to collaborate with these outmoded noxious forms of culture, but to sabotage the workings of these institutions so that their magic cleansing machinery is revealed for what it is and to build counter-institutions of solidarity with the human and nonhuman victims of the culture of industrial capitalism. It’s time we put art back into the service of life rather than death.

Of course this blog may well be censored by ZKM and you may never read these words (if that’s the case you will be reading them on another blog such as http://art-leaks.org/). But maybe, if you are reading them, then the words themselves have become part of the machinery, too weak to have any effect and easily digested. But maybe at least they will remind us that we have to stop pretending to do politics and that words are never enough.

Further information on: www.global-activism.de

About the author

John Jordan merges the imagination of art and the radical engagement of activism, creating new forms of resistance rather than representations of politics. “A magician of rebellion” is how French newspaper Liberation described him, whilst the British Government uses the label “Domestic Extremist.” He prefers what Scotland Yard said when trying to persuade an arts manager to cancel a show she had booked by The Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination (Labofii), the collective he now facilitates with Isabelle Fremeaux: “This,” the police said, “is not a normal travelling theatre company.” Infamous for launching a rebel raft regatta to shut down a coal-fired power station, turning bikes into machines of disobedience during the Copenhagen climate summit, and being censored by the BP-sponsored Tate gallery, Labofii is now setting up a commune, farm, and school for creative resistance in Brittany.

Codirector of social art group Platform (1987–1995), Jordan went on to cofound “Reclaim the Streets” (1995–2000). Senior lecturer in fine art at Sheffield Hallam University (1994–2003), he abandoned academia to work on the film The Take with Naomi Klein. In 2004 he cofounded the Clandestine Insurgent Rebel Clown Army, which became a global protest meme from which he soon went AWOL.

He is the coauthor of We Are Everywhere: The Irresistible Rise of Global Anticapitalism (2003, Verso), A User’s Guide to Demanding the Impossible (2010, Autonomedia), and the film-book Les Sentiers de l’Utopie, (2011, La Découverte).

___________________

Note

[1] Alan Kaprow, Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life, edited by Jeff Kelley, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2003, p. 218.